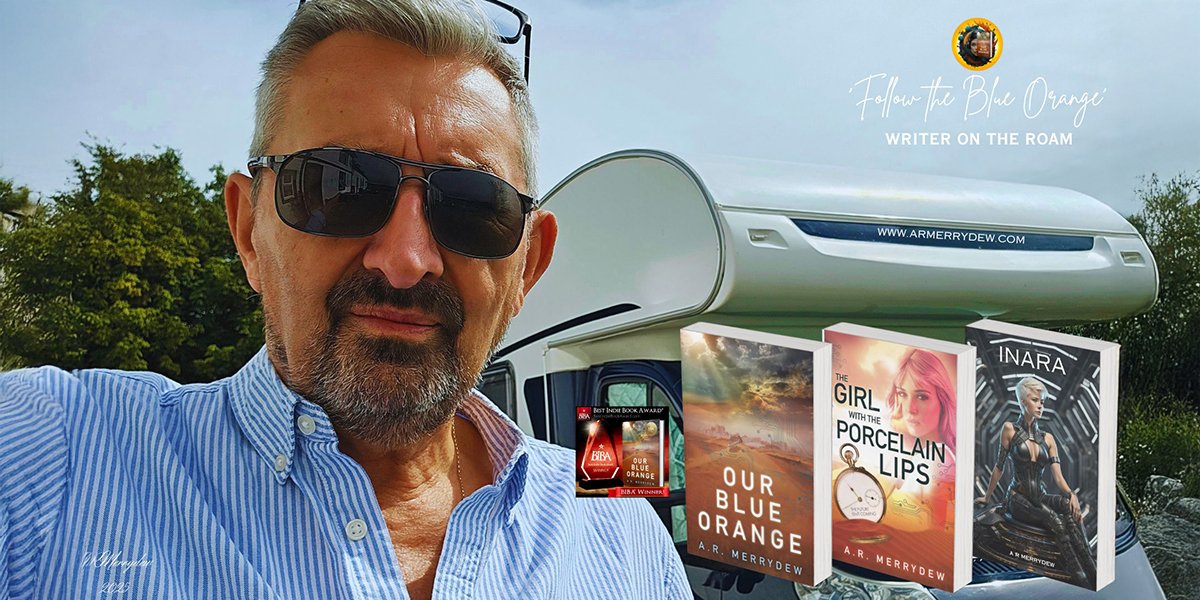

PHOTO: Anthony Merrydew writing aboard his motorhome ‘Vera2’, surrounded by tranquil views and inspired solitude.

Science Fiction, Soulful Verse, And Life On The Road

Anthony Merrydew discusses his award-winning science fiction series, poetic inspiration, motorhome lifestyle, and the creative spark behind his evolving work on AI, collaboration, and human resilience.

Anthony Richard Merrydew was born in Dorking, Surrey, England, where his early years were shaped by the quiet countryside and the ever-present allure of literature. Educated at Andrew Cairns Secondary Modern school in Littlehampton, his journey into the world of writing began with the manuscript Malakoff, penned during his time in Besancon, France. Despite remaining unfinished, this early work laid the foundation for his literary explorations to come.

Merrydew’s debut novel Our Blue Orange emerged after years of meticulous crafting, blending his fascination with automation and Artificial Intelligence into a lighthearted science fiction narrative. The accolades followed swiftly, with the novel clinching the BIBA Best Science Fiction Book of the Year Award in 2022, a milestone that reshaped his career and future ambitions.

In the aftermath of a life-altering accident in France, Merrydew retreated to Dunoon, Scotland, finding solace and inspiration on a friend’s farm while completing his second novel, The Girl with the Porcelain Lips. This period of recovery infused his writing with a poignant depth, reflecting both personal resilience and evolving societal themes surrounding AI.

His subsequent works, including Inara and the poetic collection From the Pen of an Aquarian, continued to explore the intersection of humanity and technology, each offering a unique perspective on our collective future. As he navigates life from the confines of his motorhome ‘Vera2’, Merrydew’s nomadic existence serves as a perpetual muse, capturing landscapes and moments that enrich his literary voice.

Anthony Merrydew’s journey is not just one of literary achievement but also of personal evolution, where each novel and poetic verse offers a glimpse into his introspective world. His commitment to exploring the complexities of AI and human connection resonates deeply, making him a distinctive voice in contemporary science fiction.

In Inara, you introduce new characters. How do they reflect the evolving themes of AI and societal control in your series?

In the third volume, Inara, new characters such as ‘Barbara’, or ‘Bab’s as she prefers to be called, are introduced. Her arrival on the scene is pivotal in progressing the plot, and also in developing the other characters and their back stories, such as Missouri for example. Barbara, who was originally from Earth, travels the void in an opulent craft. She not only has wealth, but a vast experience of the Galaxy, and Jack and Miranda desperately need both. Their failed attempts at prosperity on their own planet, now makes them willing students.

Our Blue Orange blends humour with dystopian elements. What inspired this unique combination in your debut novel?

Having read George Orwell’s 1984, as a teenager, the novel left its mark. It fuelled the rebel in me, which frankly at that age, took very little encouragement. Growing up in an alleged democracy, Orwell’s novel was a benchmark for me. It highlighted the deception those in control can, and do deliver over society. I could write anything I liked for example, as long as the government gave it their blessing, and not a ‘D-Notice’.

The absurdity of a democratic society has stayed with me my entire life. Great Britain no longer had the word great in it for me, as it has appeared to resemble ‘Oceania’ more and more as the years passed me by. Adding humour to an imaginary dystopian society, was a way in which to buffoon the system. The lead up to the president’s death in the Planetarium for example, was given a humorous element. As the architect of total control and mass genocide, it seemed a befitting end for such a ‘Big Brother’ stereotype.

The Girl with the Porcelain Lips was completed during your recovery in Scotland. How did that experience influence the novel’s tone and themes?

By the time the second volume began, the world had become a different place in terms of Artificial Intelligence, and its development. My world had changed too, there was at the time a lot to get over, both physically and mentally. Writing the second instalment was a much-needed distraction from my real world, and something of a game changer. The Girl with the Porcelain Lips was my most productive book to date, as I penned the last forty-two thousand words in twenty-nine days. The experience was mentally exhausting, and one I hope I never have to repeat. Writing that book will always remind me of just how far you can push the human spirit.

Your poetry collection, From the Pen of an Aquarian, explores love and darker moments. How does your poetic voice differ from your prose?

Even I would fail miserably at trying to draw any comparison between my poetry, and the stories I pen in my science fiction genre. When I read my own poems, I find myself trying to understand where they came from. I have in the past, tried to describe to friends, even complete strangers, how these words are delivered to me. There is no conscious effort, to sit down and write a poem regarding any given subject. They simply land in my mind and I write them. Interestingly, I have written virtually nothing on this front since my mishap in Rennes.

Living full-time in your motorhome ‘Vera2’, how does this lifestyle impact your writing process and creativity?

I have found that combining my writing with travelling has been truly inspirational. Wherever I have settled for the night, the camera is normally employed to record the location. This lifestyle with its freedom is truly intoxicating. Some while ago I started posting pictures of lakes, fields, castles, farms and animals, with a simple caption, ‘Writer on the Roam’ – ‘In the middle of nowhere.’ These pictorial records have proven popular, with individuals in city offices, who I am sure, yearn for a taste of the wide open spaces. There is no calendar in my motorhome. Each new day is a blessing, and it doesn’t need to have a number beside it. Finally, I am living my best life.

Your early manuscript Malakoff remains unfinished. Do you foresee completing it, and how has it influenced your subsequent works?

Malakoff was my first attempt at writing a book. I lived in France at the time, and spent many weeks in a remote farmhouse in the country. When I look back on it now after all these years, I have several thoughts. Firstly the story was plausible, though the plot was thin, and barely able to be credible. I have over the years toyed with the possibility of revamping it completely. However, for me this part completed work is like my first bicycle. It still holds some fond memories, but like most everyone else, I moved on to another bike as I grew up. In reality I fear, Malakoff will always be my unfinished symphony. The story that has, and will I think, loiter in my mind forever.

Co-authoring The Dumb Dumb’s Handbook series marks a shift. What motivated you to explore these new themes collaboratively?

It was a chance conversation, with a friend one evening in a pub, which led to a bizarre series of events. There was an opportunity to help someone else who had a passion for a subject, and wanted to craft it into a book. Someone who had a voice and needed help with getting it heard.

The Dumb Dumb’s Handbook To Recruitment Ghosting Strategies was born. The exercise actually gave me another direction, a detour from my normal work. I have developed two further handbooks so far, regarding subjects I had been ensconced in for years. They have both proven to be a wonderful way to get down on paper, what has loitered in my mind for years. There will I believe, be more to follow.

What key advice would you offer aspiring authors navigating the evolving landscape of science fiction writing?

Stay true to yourself, and the story you have to tell the world, no matter how bizarre it may seem. Listen to no one until it has been completed. Criticism during the process of writing your book can ruin the story, and the writer.