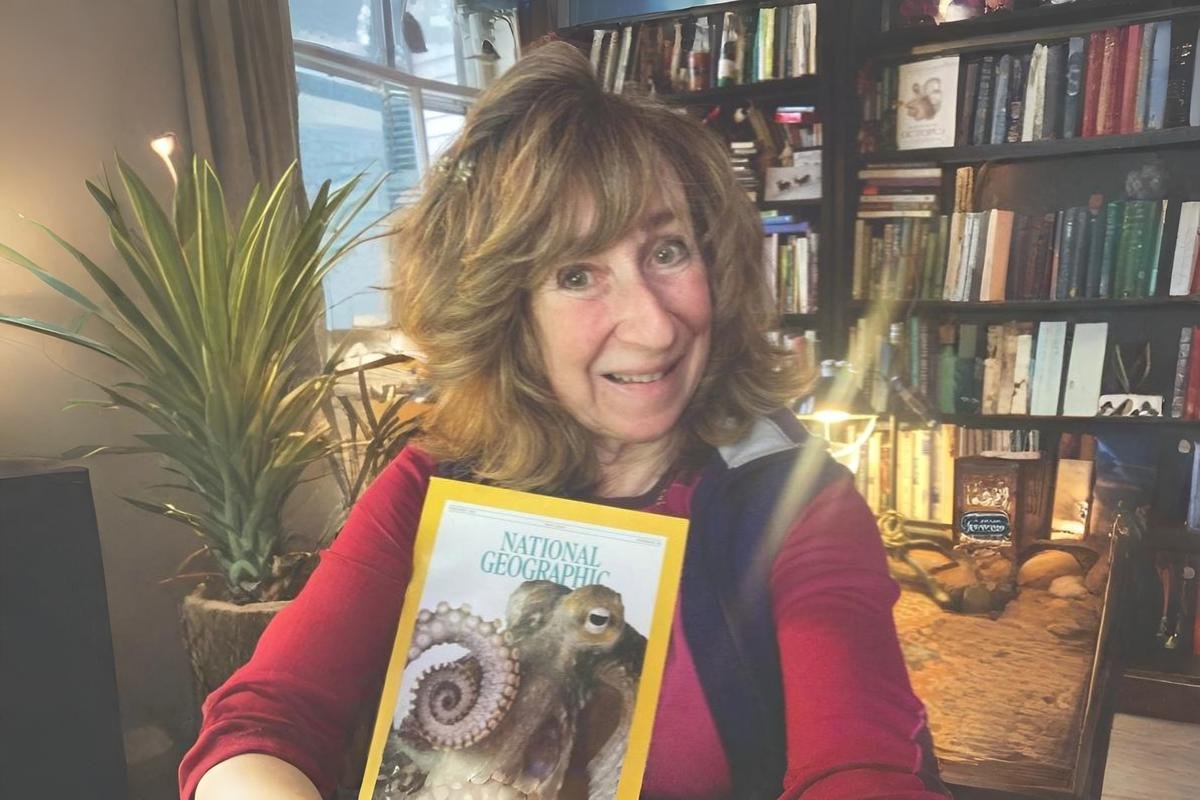

PHOTO: Sy Montgomery gently interacts with an Octopus cyania in Moorea, epitomising her heartfelt connection to the creatures she studies. Credit: David Scheel.

Unveiling Deep Connections Between Humans And Animals

Sy Montgomery shares profound insights into animal intelligence, emotional connections, and the critical need to nurture empathy for other species, blending scientific observation with deeply personal experiences in the natural world.

Sy Montgomery’s extraordinary life has been shaped by her deep devotion to animals and nature. Celebrated as “equal parts poet and scientist” by The New York Times, Sy’s writing seamlessly blends rigorous research with an enduring sense of wonder. From scaling the cloud forests of Papua New Guinea to scuba diving in vibrant marine ecosystems, each encounter with the natural world enlarges her understanding—and ours—of the connections that bind all living beings. Her works, such as The Soul of an Octopus and Of Time and Turtles, don’t merely invite readers to marvel at animal intelligence and behaviour—they challenge us to reconsider our place within the vast web of life.

What sets Sy apart is her remarkable ability to convey the delicate, profound intelligence of creatures often dismissed or misunderstood. Whether advocating for the emotional depth of a pig named Christopher Hogwood in The Good Good Pig or illuminating the social intricacies of turtles, her prose reminds us of humanity’s shared essence with what she calls the “animate creation.” Indeed, Sy’s narratives feel less like descriptions of distant beings and more like invitations—to empathy, gratitude, and stewardship.

Through vivid detail and heartfelt experiences, Sy’s work reframes the natural world as a realm of teachers. Turtles demonstrate patience and endurance, octopuses reveal ingenuity and sentience, and even chickens, in their overlooked brilliance, inspire new respect. Yet Sy’s ultimate focus isn’t simply on the animals she studies. Her books are a clarion call to adopt a new lens, one that perceives nature with humility and reverence. As she often urges, “If we fail to pay attention to our fellow creatures, we’ll rob ourselves of life’s richness.”

Sy Montgomery’s writing holds a mirror to the world we stand on, asking us to see its colours, textures, and voices with fresh eyes. Through stories of animals great and small, powerful and fragile, her work is both an act of conservation and an invitation to awaken—to the beauty of the living Earth and the urgency of its preservation.

Sy Montgomery is a literary treasure, weaving science and emotion to reveal the beauty and intelligence of the animal kingdom.

In What the Chicken Knows, how did your personal experiences with chickens reshape your understanding of these often-overlooked birds?

I always start my adventures with animals with “Beginner’s Mind.” I knew, of course, that some people dismiss the intelligence of birds, and particularly chickens, as “bird brains.” But I also knew from my life getting to know creatures from tarantulas to tapirs and from pink dolphins to pigs that humans typically underestimate the powers of those unlike ourselves. I was not surprised to find chickens are smart. But I was delighted to discover that in many ways, their smarts are so like our own. They can recognise and remember 100 different faces, including human faces. Their special mapping abilities are superb. And the pecking order is far more about order than pecking, because relationships are extremely important to chickens. They want to belong in their community or group, just like we do. They are capable of reasoning, remembering, and communicating complex information—such as whether a predator is coming quickly or slowly, from sky or land. Yet, at the same time, their instincts are sharp, and sometimes direct them to behave in ways we find baffling. At the sight of blood, for instance, chickens will attack even their closest kin. Nobody knows why they do this.

Secrets of the Octopus builds upon your earlier work; what new insights into octopus intelligence and behaviour did you uncover during this project?

So much new science has been done since Soul of an Octopus was published in 2015! One of the most exciting discoveries at least partially answers one of the questions that burned in me the whole time I was working with my octopus friends at New England Aquarium starting in 2011: why did these animals, who are famously solitary, even want to interact with me at all? As it turns out, many species of octopuses are not solitary after all. Even the Giant Pacific octopus can often be found in aggregations in the wild. Other species inhabit octopus “cities” like Octopolis in Australia, where more than a dozen individual Octopus tetricus might den in an area only 2-3 meters in diameter. Other species seem to cohabit with favoured mates. And yet more may develop partnerships with other species for the purpose of hunting together!

“Animals are great teachers who help us reconnect with life’s richness.” – Sy Montgomery

Your memoir How to Be a Good Creature intertwines personal stories with animal encounters; how have these relationships influenced your perspective on human-animal connections?

That book tells the stories of how 13 animals taught me so many of the most important skills of my life: how to find what you want to do with life. How to find the path to lead you there. How to forgive someone who has hurt you. How to make a family. (Hint: it’s not about genes or blood; it’s about love and not confined to just one species!) My relationships with animals have shown me that animals are, just as native peoples around the world have known for eons, great teachers. If we fail to pay attention to these other creatures around us, and concentrate our attention on humans alone, our lives will be as impoverished as if we only listened to one kind of music, ate one kind of food, and never left our own room.

In Of Time and Turtles, what lessons did you learn about resilience and healing from working with injured turtles?

Turtles survived the asteroid impact that killed off the dinosaurs. They survived the Ice Ages. Each turtle who lives to adulthood has survived a gamut of predators, from raccoons, dogs, and skunks who dig up their eggs to crows and herons and chipmunks, who eat the hatchlings. And a turtle may well survive an injury that would surely kill another creature. Turtles teach you to have faith. Turtles teach you to cultivate patience. And helping turtles—literally repairing broken shells—showed me the renewing power of taking a hand in healing our broken world.

The Soul of an Octopus explores consciousness in cephalopods; what challenges did you face in conveying their inner lives to readers?

The challenge one faces is the notion, pervasive in Western culture, that only humans have thoughts, feelings, memories, and knowledge. Which is of course absurd if you accept the evidence for evolution: being able to think and feel, to learn from experience and plan for the future, has obvious adaptive value for many organisms, not just our kind. So I followed the advice that guides every good journalist: show, don’t tell. I wrote about my octopus friends’ behaviour—and generally let readers draw their own conclusions.

“Communing with creatures reminds us of the delicate and shared essence of all life.” – Sy Montgomery

Your adventures often involve close interactions with wildlife; how do you balance scientific observation with personal engagement in your narratives?

The narrative provides a scaffolding for the science. Of course the science is interesting on its own—that some turtles communicate with one another while still in the egg, that many species learn mazes as fast as lab rats, that some sea turtles’ shells glow in the dark. But it means so much more when it applies to a specific individual who you have come to know over the narrative journey of the book.

Having written for both adults and children, how do you adapt your storytelling approach to suit different audiences while maintaining authenticity?

Many of my books written for younger audiences—including those I wrote for the Scientists in the Field series I founded with photographer Nic Bishop—are reviewed as if they were written for adults. Kids are smart. Because they haven’t been alive as long as adults, their vocabularies are smaller, and their knowledge about the world less extensive. But other than this I think we’re largely the same. I use shorter and fewer words in my books for kids. But I respect their smarts and honour their curiosity just as I would a smart adult’s. One of the smartest and most experienced people I know is the Emmy award winning actor and podcaster Alan Alda. He’s been alive for nearly 9 decades. He’s had his own science TV show. Do you want to know his most pressing question when I introduced him to New England Aquarium’s resident Giant Pacific Octopus?

“Where does its poop come out?” (Answer: from the siphon it uses to jet through the sea.) I think most adults are in fact interested in knowing such things but aren’t brave enough to ask out loud!

“Octopuses show us that intelligence and emotions come in forms wildly different from our own.” – Sy Montgomery

What advice would you offer to aspiring authors aiming to write compelling narratives about the natural world?

Go out and live in the real world—the sweet, green, living world—be it in your backyard or in some exotic location. Just pay attention. What does it smell like, feel like, sound like to be in this place at this time with these creatures? How do they make you feel? And when you write, think of writing to a dear friend, knowing that every vivid detail you bring back from your experience to share is a gift to them, and a love song to this splendid, fragile, incandescent life.