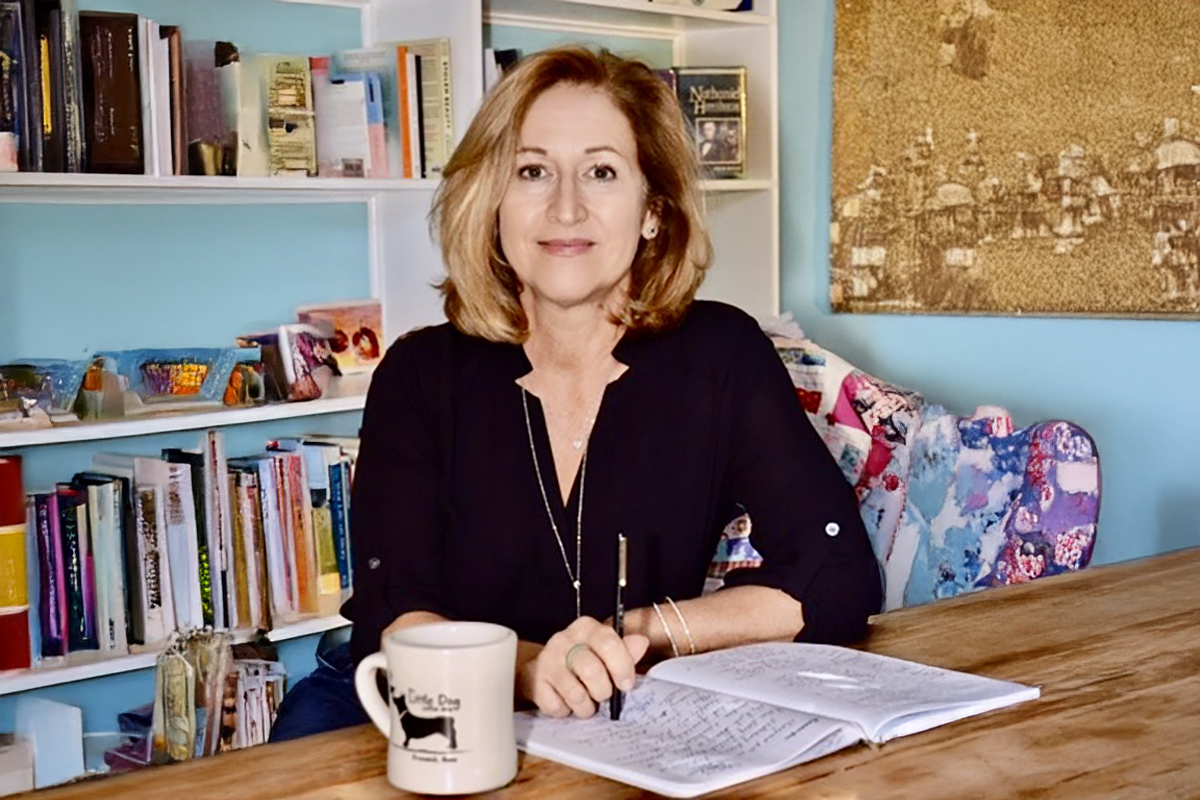

PHOTO: Laurie Lico Albanese smiling warmly, seated with a stack of her novels and notes, exuding thoughtful creativity and quiet confidence.

Feminist Voices Historical Fiction Artistic Resilience

Laurie Lico Albanese discusses giving voice to overlooked women, exploring historical resilience, blending research with storytelling, and transforming ordinary lives into vivid, sensory, and profoundly human narratives.

Laurie Lico Albanese writes with a rare intimacy for history, drawing us into worlds both meticulously researched and vividly imagined. In Hester, she gives voice to Hester Prynne, the iconic figure of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter, exploring the shadows and splendours of 19th-century Salem through the eyes of Isobel Gamble, a young woman whose extraordinary synaesthesia transforms embroidery into a language of survival and self-expression. Albanese’s prose carries the weight of history without ever feeling heavy, allowing her characters’ inner lives to bloom in colour and texture.

Her previous works, including Stolen Beauty and The Miracles of Prato, display the same devotion to illuminating women’s lives against complex historical backdrops. Whether tracing the fates of Adele Bloch Bauer and her niece Maria in Vienna or navigating the intimate landscapes of personal desire and creativity, Albanese brings a clarity and empathy that lingers beyond the page. There is an artistry in the way she balances historical fidelity with a contemporary sensitivity, turning archival research into living, breathing stories.

Albanese’s fascination with forgotten or overlooked women is evident throughout her work. She is drawn to the resilience of those who confront societal constraints, oppression, and the turbulence of their times, crafting narratives in which courage, creativity, and identity intertwine. In doing so, she invites readers to witness not only the historical moment but also the enduring relevance of these women’s struggles and triumphs.

Her approach is as much a study in the human spirit as it is a celebration of historical detail. Every texture of fabric, every carefully observed gesture, and every imagined interior monologue becomes part of a larger exploration of voice, agency, and survival. In Albanese’s hands, history is not merely remembered—it is made intimate, sensory, and profoundly alive.

In Hester, Isobel Gamble’s synaesthesia guides her creative expression—how did you develop this sensory trait and what role does it play in shaping her voice?

The novel began with two simple questions: what if there was a real Hester Prynne, and what if she could tell her own story? Since Isobel is a fictional character, the challenge was creating a believable 19th century voice for a young Scottish woman who allows herself to be seduced by a moody author when her husband leaves her alone in Salem. The poetry in Isobel’s voice and her creative vision took on a life of their own, bolstered by reading fiction from the period and by watching “Outlander”! I read extensive biographies of Hawthorne, which helped with period details and social norms.

Isobel’s embroidery becomes more than craft – it’s storytelling and survival. How did you research the historical and symbolic importance of needlework in early 19th century Salem?

Much has been written about the history of needlecraft through the feminist lens, especially The Subversive Stitch by Rosika Parker. I also found a wealth of beauty and information in Salem’s Peabody Essex Museum and their stunning book, Painted with Thread: The Art of American Embroidery. Many of the embroidered objects in Hester come directly from this book.

You reimagine the muse behind The Scarlet Letter. What inspired you to explore Hester Prynne’s backstory from a feminist perspective, and how did you balance historical fidelity with fresh character depth?

Once I discovered she had synesthesia it allowed her voice to bloom with sensory details.

Stolen Beauty intertwines Adele Bloch Bauer’s and Maria Altmann’s stories. How did you navigate writing across two timelines and ensure both women’s voices resonated with equal power?

Both Adele (the subject of Gustav Klimt’s famous Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer 1) and her niece Maria were strong-willed and courageous women. Their challenges are determined largely by the times in which they live—Adele confronting the disenfranchisement faced by even the wealthiest women in early 20th century Vienna, and Maria losing everything to the Nazis when she flees Austria in 1938. To balance the timelines I had to make a detailed parallel outline, but otherwise it wasn’t difficult at all, as their stories are natural counterpoints to one another, and both women discover their true purpose through the portrait.

Themes of art, truth and identity permeate Stolen Beauty. How did researching Klimt and post WWII Austria influence your portrayal of beauty as resistance?

I see the story of the Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer 1 as one of creation, near destruction, and resurrection. Viewed through this lens, the painting become the vehicle for Maria and Adele’s discovery of their identities and the sources of their courage. Klimt was part of the Austrian Secession movement, and at the entrance to the Secessionist gallery in Vienna is the phrase, “To Every Age Its Art; To Every Art Its Freedom.” This too became a theme of the novel, as the famed painting is stolen by the Nazis and the Secession Building is hung with swastikas during the war. The accumulation of great art was central to one of Hitler’s missions, and in the end justice prevails.

Both Hester and Stolen Beauty highlight women’s resilience under oppression. What draws you to exploring female strength and agency across different historical contexts?

I’m fascinated by the stories of forgotten or under-represented women. Since the history of women is largely the history of oppression, it wasn’t hard to find colorful stories to pique my interest. These stories feel relevant to me now in today’s world; I see Isobel Gamble’s as a sort-of “Me-Too” story, and Adele’s and Maria’s trajectories as one of finding strength despite sexism and other obstacles that men and history put before them. The political is personal, especially in Stolen Beauty.

As someone with a background in journalism, travel writing and teaching, how have these experiences enriched your narrative style in historical fiction?

Writing historical fiction can be a great adventure, and that’s how I treated the writing of these novels, travelling to the countries and places where they take place and doing research there and at home. As a teacher I also like to look for the story behind a work of art, and that’s what I’ve done in both of these novels. You spend years with these subjects and characters and so it’s important to be fascinated by the time and place, which I am.

Finally, what one piece of advice would you offer aspiring authors aiming to write historically grounded, character driven fiction based on real figures?

Be sure the time and the people fascinate you, and do as much research as you can…then make sure very little of your research efforts appear on the page. Beware of info dumping what you’ve learned. Just tell the human story and let the details you discover speak for themselves.