PHOTO: W.D. Kilpack III, award-winning author and storyteller, known for blending philosophy, mythology, and visceral human experience into his acclaimed science fiction and fantasy sagas.

Award-Winning Author Blends Philosophy Myth And Human Experience

W.D. Kilpack III reflects on the inspirations behind his novels, the influence of wrestling, cultural research, and how authenticity, philosophy, and endurance shape his award-winning science fiction and fantasy worlds.

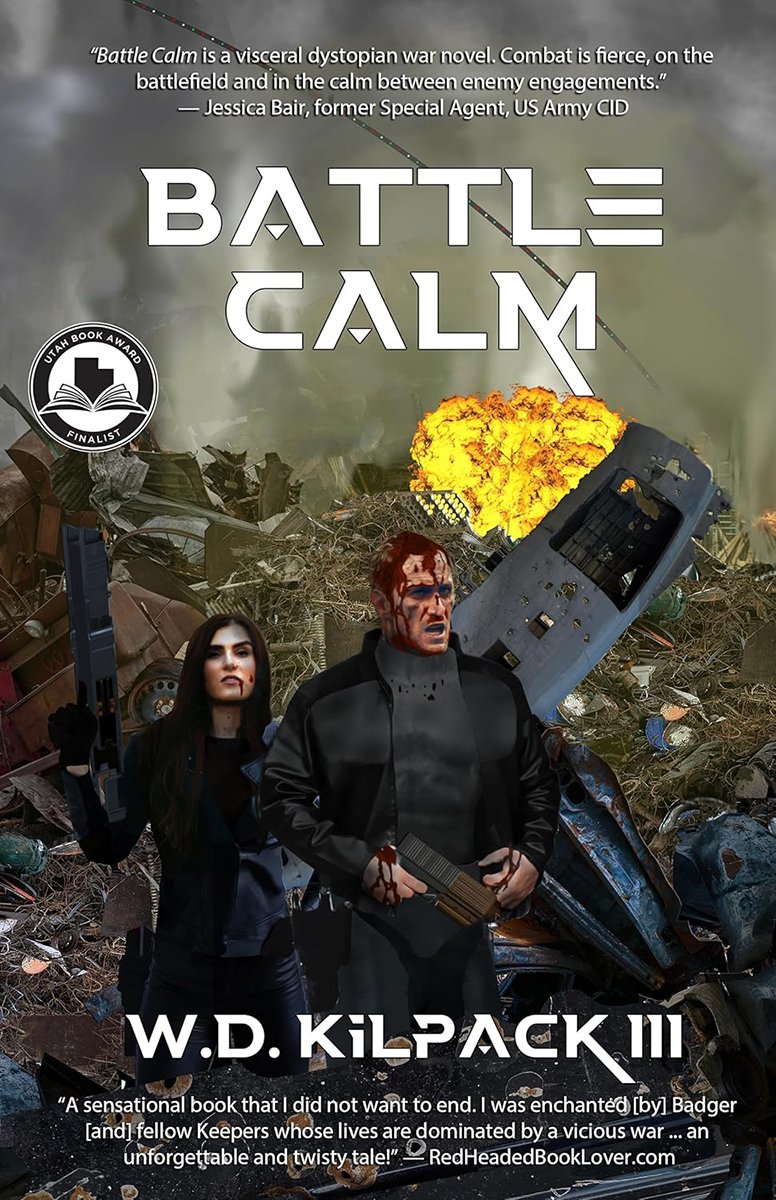

W.D. Kilpack III is a storyteller whose imagination refuses to be contained by a single medium. From the New Blood Saga to the Battle Calm Cycle, his work fuses philosophy, myth, and visceral human experience into worlds that feel at once ancient and startlingly alive. His novels, rich in moral complexity and brimming with physical immediacy, have earned more than forty-five literary awards — a testament to their enduring resonance with readers across genres.

What makes Kilpack’s writing distinctive is not only his mastery of craft, but the lived intensity that informs it. A former elite wrestler and coach, he brings to his characters the scars, resilience, and raw determination forged on the mat. Battles in his books are never mere spectacle; they are imbued with psychological weight, with every strike carrying the echo of personal sacrifice. That same authenticity extends to his cultural research, where respect and empathy guide his depictions of Native American traditions and belief systems.

Beyond the page, Kilpack’s career has been remarkably multifaceted: journalist, editor, publisher, screenwriter, professor. Each role has sharpened his sensitivity to words, rhythm, and voice — skills he continues to refine by reading his work aloud to his first and most trusted critic, his wife. Yet, for all his accolades, he remains a writer deeply committed to the emotional heart of storytelling: to move readers, to make them feel, to leave them changed.

Kilpack’s journey is one of persistence, adaptation, and a relentless pursuit of authenticity. His stories remind us that courage is not only found in the grand sweep of battle or the clash of empires, but in the intimate struggle to live truthfully, to create meaning, and to endure.

What was the moment you realised Red Skin’s Laws could become the moral backbone of an entire cycle of novels?

There were several books that used little snippets of wisdom or songs or even poetry at the beginning of each chapter that really struck me growing up. One was The Coming of the Horseclans by Robert Adams; another was Santiago by Mike Resnick; but the one that really struck home for me was Jhereg by Steven Brust. In each case, using these brief statements at the beginning of each chapter might give some insight into particular characters in that chapter, but always made a major contribution to the world-building that I really enjoyed. Brust made me want to incorporate something along those lines into some of my own storytelling because his snippets were so smart, so biting and, often, very witty. At the same time, I enjoyed philosophy, and found two philosophers whose entire works were often made up of these types of snippets, Nietzsche and Boethius, when I got a bachelors degree in philosophy. So all of this created layers of influence on Red Skin’s Laws over many years. However, “the moment,” came in 1985, when I wrote the first draft of Battle Calm. I was 14 and I watched the first thirty seconds or so of The Terminator on VHS, turned it off, and started writing about a world that had been at war for so long that no one could remember a time when it was not. At that time, it was a single, standalone book. Most of Red Skin’s Laws were written then, in 1985. I made rewrites over the years, including a much more expansive revision after interviewing some military veterans to get a more realistic feel for life in the trenches. That led to more chapters, which required more Red Skin’s Laws.

How did your own experience as a wrestler and coach inform the physicality and psychology of Badger and the Keepers?

Wrestling is the hardest sport there is. To have any kind of success requires a certain mindset and approach to life that includes a high level of endurance, resilience, and self-drivenness. I’ve heard it said a lot of different ways: “wrestlers are a different breed” or even “wrestlers are a totally different species.” This approach to life is often the inability to accept defeat. I wrestled for 12 years and, of course, I lost matches. However, I don’t typically say I lost to so-and-so. What I usually say is, “It took me three years to finally beat him” or something along those lines. Personally, any challenge in life, regardless of where it takes place, is viewed as an opponent that must be beaten. Defeat is not an option. Even if there is a loss, it’s only temporary, and the loss is a good thing if something was learned in the process. One of Red Skin’s Laws is a direct result of my philosophy as an athlete and a wrestling coach: “Red Skin’s Laws, number ten, strength is not most important in a fight; it is not strength that survives, but cunning. If there is any doubt in how to proceed, then attack. Nine out of ten battles, the attacker achieves victory.” My goal as a coach was for every one of my wrestlers to be a technician, to execute their techniques correctly. Yes, they need to be strong, in good condition, mentally tough, be able to endure pain, etc., but all of those things can be developed in any athlete to some degree. When all things are equal, the one who does it right wins. If both are doing it right, nine out of ten times, the aggressor wins. So wrestle smart. I have written a syllabus of wrestling moves, breaking them down so that a 4-year-old can understand them or an adult. This feeds into my action scenes and the descriptions of what’s happening. In addition, as a high-performing athlete (I qualified to represent the USA in Greco-Roman wrestling), I have sprained, dislocated, torn, or broken just about anything you can name at least once. I have broken my nose nine times. I have had nine shoulder dislocations and now have two screws in one shoulder. I’ve had three knee surgeries (my left knee ended my career). I’ve been knocked out more than fifty times. I bit off the edge of my tongue. I laid my front teeth back against the roof of my mouth. I wrestled 3 minutes with a shoulder so badly dislocated the trainer could not get it back into socket. I once had a concussion that left me unable to walk for ten days and erased memories from throughout my life (some of which never returned). I can tell you if it’s going to rain or when the rain is going to clear out, based on the type of ache in my knees. I have detached ligaments in both thumbs and had to teach my five children not to grab my thumbs to keep them from popping my thumbs out. I cut so much weight that I damaged my liver and my metabolism. I still bawl my eyes out every opening and closing ceremony of the Olympics because I missed my window for that level of competition due to injury. I’ve had five surgeries in the past ten years as old injuries have caught up with me. Those things affected my life and still do, physically, emotionally, psychologically, and I use those scars to add color to my characters.

When you discovered the Omega Message within the narrative, did it alter your original outline for the Battle Calm Cycle?

That’s not a strictly yes-or-no answer. I do not outline my books; however, I have milestones in mind. The story fills in the steps between those milestones. Stephen King said, “A good novelist does not lead his characters, he follows them.” There’s more to that quote, but you get my point. When I write, I love the moment when I sit back and think, “Whoa! I didn’t see that coming!” But when it’s something like the Omega Message, it’s not that it exists that is the surprise (that was a milestone from the beginning) but how it exists. When I’m writing, if I have an idea that someone else has done in some way (or many others), then I try to find a way to take that same event but flip it on its ear, approaching it from the opposite direction. So the discovery of the Omega Message did not alter the narrative; the elements surrounding it were not what I saw coming and that did affect my narrative. It provided additional backstory for some characters, some additional conflict, some additional internal struggle, which flavored the rest of the narrative.

Which scene in Rilari left you emotionally drained after writing it, and why?

When I started writing the New Blood Saga, I had three things: a recurring dream for several months that would wake me up in tears; a character idea that I wanted to use since I came up with it while in college; and a map I had been experimenting with. (Previously, all my maps were hand-drawn; this was my first purely computer-drawn map.) With those three things, I started writing. However, when dreaming, all the gravitas is inherent. You know it all, you feel it all, it all exists as part of the package. When writing a novel, you have to create the events that build the backstory and characters and history that creates all of that gravitas. It started out with the plan of writing one book. I soon realized that was impossible to achieve the power of the dream. So I planned on writing a trilogy. Then I realized that I wouldn’t even reach the dream by the end of book three. So I decided that, with the results of the dream (what came after), I would write a six-book series. When I was in book six, it was feeling rushed, so I decided it would be eight books. The dream that was the main inspiration for the New Blood Saga takes place at the end of Rilari. Writing it was very difficult, because I had to keep taking breaks to stop crying. Then I had to go back and fix the typing errors, because I taught myself to type, and actually look at the keys when typing, so I made mistakes when trying to type with blurred vision while crying. Writing that scene was extremely difficult to write, emotionally draining, emotionally and psychologically exhausting, yet still gratifying, because I knew that I had achieved something. If it had me bawling, I knew it would affect my readers similarly. That is one of my goals when I write: getting an emotional response.

Could you share the research path you followed to weave Navajo mysticism so authentically into Pale Face?

I was very young when my grandma told me that I am part Cherokee. She was the family genealogist and she told me about him and how you could see the Cherokee in us in our prominent cheekbones. As a result, I have been fascinated by Native American culture since a very early age. When I was 10 years old, a school teacher gave us a project about our lineage and everyone said what they were. I very proudly declared, “I’m German-Irish-Cherokee!” (Which was not exactly correct, but that’s a different story.) Even when that young, I did not watch a lot of Western movies (an exception was A Man Called Horse) or read Western novels, but I read a lot of history and stories about different Native American tribes. Visiting the Little Big Horn Battlefield as a kid had a profound effect on me. I wrote Pale Face for the L. Ron Hubbard’s Writers of the Future Contest, which had a word limit. (I had to write something new, because all of my other stuff was too long.) I wanted to write something with a Native American main character. My original intent was a Cherokee, but I also wanted to write a sci-fi story with UFOs and aliens, which meant it had to be in New Mexico. There is not a Cherokee reservation in New Mexico. However, I had driven through the Ramah Indian Reservation, which was Navajo, so I went with that. The research was much more challenging than expected, because Navajo culture is different from most of the Native American studies I had already done, and Navajo research materials are harder to find. So I spent a lot of time in my college library poring over books about the Navajo, reading and making notes. Around this time, the Western movie was revived, with the Navajo character Chavez in Young Guns, which led to a greater appreciation for Native Americans in the new generation of Westerns. (Today, Dances With Wolves is one of my favorite movies.) Yet being so limited in resources available at the time forced me to really focus and dig into what I had. It made me appreciate it that much more. That being said, making it feel authentic is one of my goals in everything I write. I want it to always feel realistic, even when I write fantasy (I call what I write “realistic fantasy”). The easiest way to write something that feels authentic is to be able to empathize and relate. I definitely feel the Cherokee in me. In high school, I bought a t-shirt that said, “In 1492, the Indians discovered Columbus lost at sea.” I wore that shirt until it couldn’t be worn anymore. More recently, I saw a t-shirt somewhere that said, “I may not be full blood but, in my heart, I’m 100% native.” If it would have been on the shelf in the store (rather than someone wearing it), I would’ve bought it there on the spot.

Having edited 23 publications with vast circulations, what editorial lesson do you now value most when polishing your own fiction?

This is the easiest question here: I read my work out loud. I instructed my college students to do the same with whatever they may write. My ear will pick things up that I might miss on the screen, so I read my books to my wife. She calls them her bedtime stories. She is also the reason why I’ve had critics say that my female characters don’t read like they were written by a man. She has a degree in psychology. My favorite comment from her is when she says, “I don’t think that character would say that” or, even better, “I don’t think that character would say it like that.” The latter almost always refers to a female character’s dialogue.

How do you balance the demands of screenwriting at Safe Harbor Films with the solitary craft of novel writing?

The two are not all that different for me. To me, writing is writing. I’ve been a journalist, a proposal writer, a technical writer, a marketing writer, a screenwriter, and more. I have said this more than once on the job: “Teach me the format you want, and I’ll do it.” By far, the most publication credits I’ve had are in news. However, the most awards I’ve received (based on percentage) is with my novels. As a journalist, I have received hate mail; as a novelist, nothing even close to that has occurred (knock on wood). Screenwriting is just another type of writing. I’m a writer. It’s like learning another style of wrestling. Just teach me the rules and put me out on the mat, I’ll be fine.

What single piece of advice would you give to fellow authors trying to juggle day jobs, family life, and the pursuit of award-winning fiction?

I am in a continuous state of creation, but have had to make repeated adjustments throughout my life, including putting goals on the back burner, adjusting sleep schedules, getting family involved, and modifying career goals. I started out as a freelancer, then a journalist, then went into PR/marketing (what I called “sellout journalists”) when I couldn’t give my kids the kind of life I wanted them to have a journalist. I then put my novels on the back burner (one of the hardest decisions of my life) until my kids were raised due to lack of time with work and coaching my kids in wrestling. I only got to dive into the deep end with my novels after my youngest finished his bachelors degree. That’s my advice: pivot when you have to, because you will.

EDITOR’S CHOICE

An emotionally charged and action-packed masterpiece, Battle Calm delivers thrilling battles and profound insights into humanity’s relentless pursuit of war.