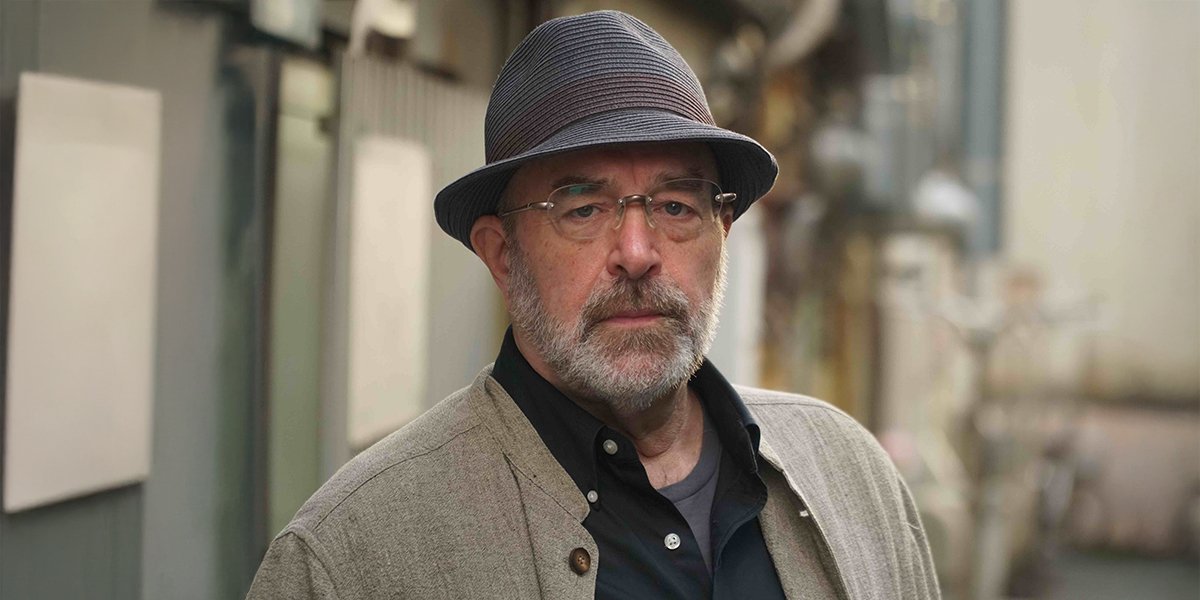

PHOTO: Michael Pronko in Tokyo, where the city’s vibrant culture, mysteries, and jazz rhythms inspire his award-winning fiction and essays.

Blending Fiction and Reality in the Heart of Japan

Michael Pronko discusses his Detective Hiroshi series, Tokyo’s complexities, jazz’s influence on storytelling, and balancing academia with writing. He offers insights into crime fiction, cultural authenticity, and the craft of narrative.

Michael Pronko’s literary craft is as intricate and layered as the city that inspires him. A master of Tokyo-based crime fiction, Pronko’s Detective Hiroshi series has captivated readers with its atmospheric depth, razor-sharp detail, and immersive storytelling. From the political tensions of The Moving Blade to the intricate scams of Shitamachi Scam, his novels do more than entertain—they unveil the unseen corners of Japan’s bustling capital with a keen, almost cinematic eye.

Beyond his crime fiction, Pronko’s Tokyo Moments series offers a contemplative, lyrical exploration of Tokyo life. His essays, collected in books such as Beauty and Chaos, capture the pulse of the city, dissecting its rhythms with the precision of a seasoned observer. Whether in fiction or nonfiction, his work is a testament to the symbiotic relationship between place and prose—each feeding into the other to create narratives rich in authenticity and nuance.

An esteemed academic, Pronko teaches American literature at Meiji Gakuin University, where he delves into contemporary novels, crime fiction, and film adaptations. His passion for jazz—evident in both his writing and his acclaimed Jazz in Japan website—infuses his work with a musicality that echoes the improvisational spirit of his storytelling.

In this interview, Michael Pronko discusses his inspirations, his deep connection to Tokyo, and the intricate process of crafting narratives that transcend cultural boundaries. His insights into crime, society, and the craft of writing offer a fascinating glimpse into the mind of an author whose work continues to shape and redefine modern crime fiction.

Michael Pronko masterfully blends crime fiction, cultural insight, and poetic storytelling, creating narratives that reveal Tokyo’s depth, intrigue, and relentless energy.

How has your extensive experience living in Tokyo influenced the development of Detective Hiroshi’s character throughout the series?

I suppose I meet him halfway. Detective Hiroshi is Japanese but lived in America for years. I’m American and have lived in Japan for years. In the novels, he has occasional culture shock, and I have it regularly. His being a little bit “outside” of traditional Japanese culture is similar to my perch in Japan—in it but not of it. I’ve had a lot of “returnee” students over the years who lived abroad for some part of their youth, and I also teach many students of mixed parentage, so I’ve learned a lot from how they see Japan. All of that filters in together. Hiroshi and I both stand in awe of Tokyo’s massive size and ceaseless energy.

In ‘The Moving Blade,’ you delve into the complexities of Japanese-American relations. What inspired you to explore this theme, and how did you approach its portrayal?

It’s in the news every week. And pretty much has been since the end of World War II. The US has fourteen large, active bases in Japan. American service personnel stationed in Japan are subject to American military law under SOFA (Status of Force Agreements) but not Japanese law. The US military controls Tokyo’s airspace. All of that sets up tensions I wanted to capture in the novel. Novels, especially mysteries and thrillers, can explore places off-limits to most people. The victim in the novel is an American who lived in Japan for years but got caught up in the history of Japanese-American relations. I think that’s another thing novels do—create a personal story that embodies a meta-story.

‘Shitamachi Scam’ focuses on scams targeting older people in Tokyo’s traditional districts. What led you to address this issue, and what research did you undertake to depict it authentically?

Ripping off older adults is such an outrage. You have to be completely heartless to cheat some of the most vulnerable people in society and ruin the rest of their lives. In Asia, respecting the elderly is a classic Confucian virtue, which makes it even worse. These crimes occur daily, but the criminals have their backstories, too. Several friends’ parents were scammed, and my local crime email list is almost all about scams. You can see signs posted at banks, convenience stores, post offices, and everywhere monetary transactions occur. I pored over news articles, in-depth reports, and police statistics, which were not hard to find. I also spent a lot of time in shitamachi, the old section of Tokyo, which is delightfully different from the rest of the city.

Your essays, such as those in ‘Beauty and Chaos,’ offer deep insights into Tokyo life. How does your essay writing inform your fiction, and vice versa?

For me, essays and novels overlap in many ways. Novels use some essay-like elements, such as ideas, evidence, reasoning, and argumentation, but they tuck them under the surface events of the story. And likewise, essays often incorporate narrative elements like character, symbolic patterns, and settings that are basic to fiction. I use narrative elements to bump up the essays and vice versa. Each sharpens the other. In essays, I can express my thoughts and opinions about Tokyo directly, but novels let me express countless reactions through diverse characters totally different from me.

Having written both essays and novels about Tokyo, how do you decide which medium best suits a particular story or observation about the city?

Day to day, it decides itself. I’ll see something in Tokyo and think, “That’d be a great essay,” and I’m off and writing. That’s always a revelation or instant insight that fits the size and shape of an essay. Other times, I think, “That’d be great in a novel,” because it’s more about how that place, part of town, experience, observation, or conflict fits onto a larger canvas. I like the sharp focus of essays, but novels are roomier and more flexible. Essays express truths succinctly and metaphorically, but novels spin truths into extended conflicts and multi-dimensional characters. Sometimes, I jot down notes for an essay, but they end up in a novel, and vice versa. But usually, the raw material falls into its own shape.

“Essays express truths succinctly and metaphorically, but novels spin truths into extended conflicts and multi-dimensional characters.” – Michael Pronko

As a professor of American Literature at Meiji Gakuin University, how does your academic background influence your narrative style and thematic choices in your novels?

An academic background is both a help and a hindrance. As a professor, it’s all too easy to overthink a story and analyze it to death. On the other hand, as a writer, it’s easy to get tangled up in emotions and enthusiasm. I try to balance the two so that they accentuate (or maybe compensate for) each other. My academic experience of outlining novels and films, engaging in discussions with students, answering their questions, and reading their essays helps me see the works from a reader’s and a student’s point of view. Writing novels expands my teaching techniques because I can draw on the process of creating from the inside. That helps me lead students toward grasping the themes and deeper structures, which in turn helps me understand how to infuse themes, ideas, and criticisms into my writing. William Carlos Williams wrote a wonderful essay about how being a doctor helped him write poetry, and writing poetry helped him be a better doctor. Exactly.

Music, particularly jazz, is a recurring element in your work. How does jazz influence your storytelling, and do you see parallels between jazz improvisation and writing fiction?

Improvisation is my go-to metaphor to explain everything. Writing is largely winging it at first, or at least improvising on a set of themes. I write a solid outline at some point, though, upon which I improvise scenes, dialogue, descriptions, and connecting elements. Jazz improvisers and writers have internalized a set of structures to tell a story. There is an early improvisational stage in writing, brainstorming, notetaking, drafting, or whatever, which is very free. However, that free, open “soloing” is layered over a set of “chord changes” like on a jazz lead sheet where the melody, rhythm, and chords are noted. The paradox is that the more structure you have, the more you can improvise. And the more you improvise, the more structure recedes. Of course, once a novel is completed, it becomes set in stone (or paper), just like jazz is set in vinyl (or digitalization). Improvisation is at the heart of all creativity, yet humans are also pattern-loving creatures. That tension proves continually productive.

What advice would you give to aspiring authors aiming to authentically portray a culture different from their own in their writing?

I think curiosity and humility are essential when writing about another culture. Curiosity drives you to discover more, but humility reins you in from thinking you understand everything. You can write from any point of view, but you should know where you stand. “My first time in Paris” could be authentic, but it would be a different kind of authenticity from “My fifty-year career in Paris.” Authenticity is usually rooted in the identity formed in one’s primary culture, but it also comes from reading, traveling, working with people, working in a system, careful observation, and paying attention to where you are in the world. It’s essential to remain a student of the culture and refrain from hasty judgment. Culture is like a Japanese garden. You can’t see it all at once, and when you move to a different spot, what you saw before becomes hidden. I think it’s crucial to let observations steep for as long as possible and not to impose conclusions before they’re ready.

EDITOR’S CHOICE

A gripping, atmospheric thriller with rich cultural depth, sharp plotting, and compelling characters. The Moving Blade is a masterfully crafted crime novel.