Rootlessness, Noir, and the Art of Reinventing Worlds

Leonce Gaiter discusses how his dynamic upbringing, historical imagination, and love of jazz inspire his bold, character-driven narratives that seamlessly explore race, identity, and societal dynamics across thrilling worlds.

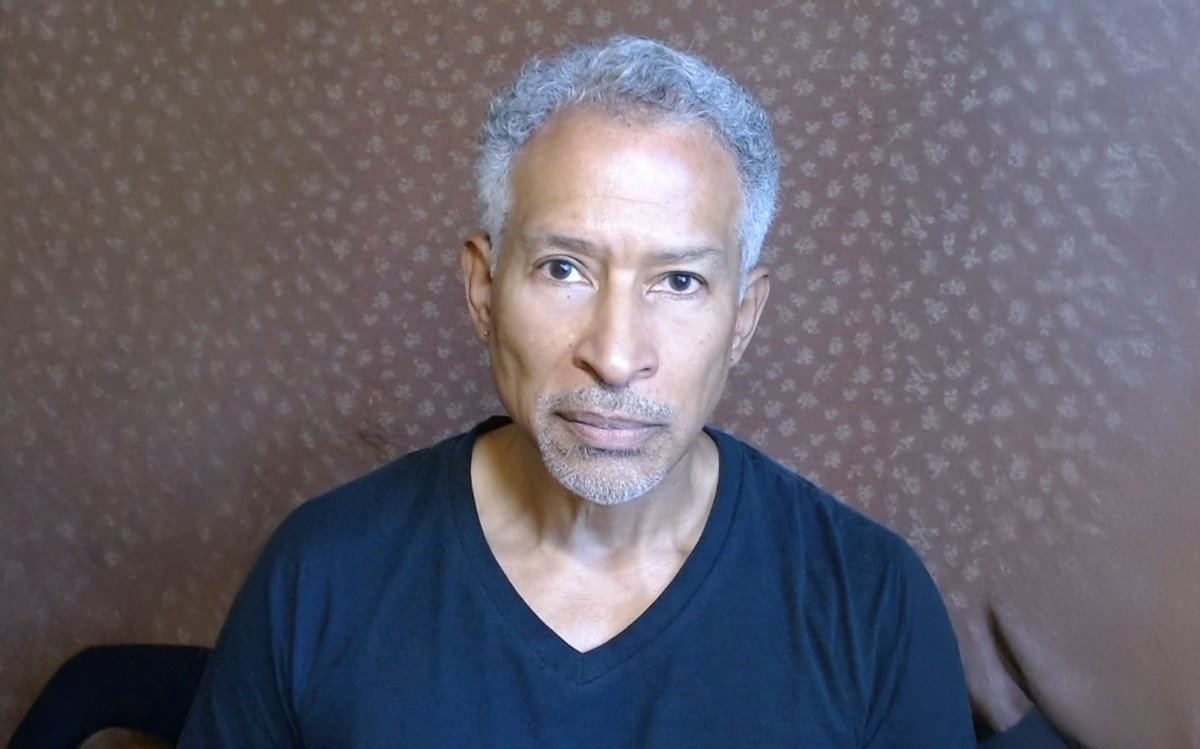

Leonce Gaiter stands as a consummate storyteller, deftly weaving together complex characters, morally intricate narratives, and vibrant, deeply evocative settings. Boasting a career that spans multiple creative spheres—from literature to film, music, and even tech—Gaiter brings an unparalleled richness to his work. His prose is bold and unapologetic, unearthing the raw, unresolved tensions of race, power, and identity through the lens of history, noir, and psychological depth. Titles such as I Dreamt I Was in Heaven – The Rampage of the Rufus Buck Gang, Bourbon Street, and In the Company of Educated Men demonstrate his gift for reimagining historical moments and unflinching human truths, presented with cinematic flair and intellectual vigour.

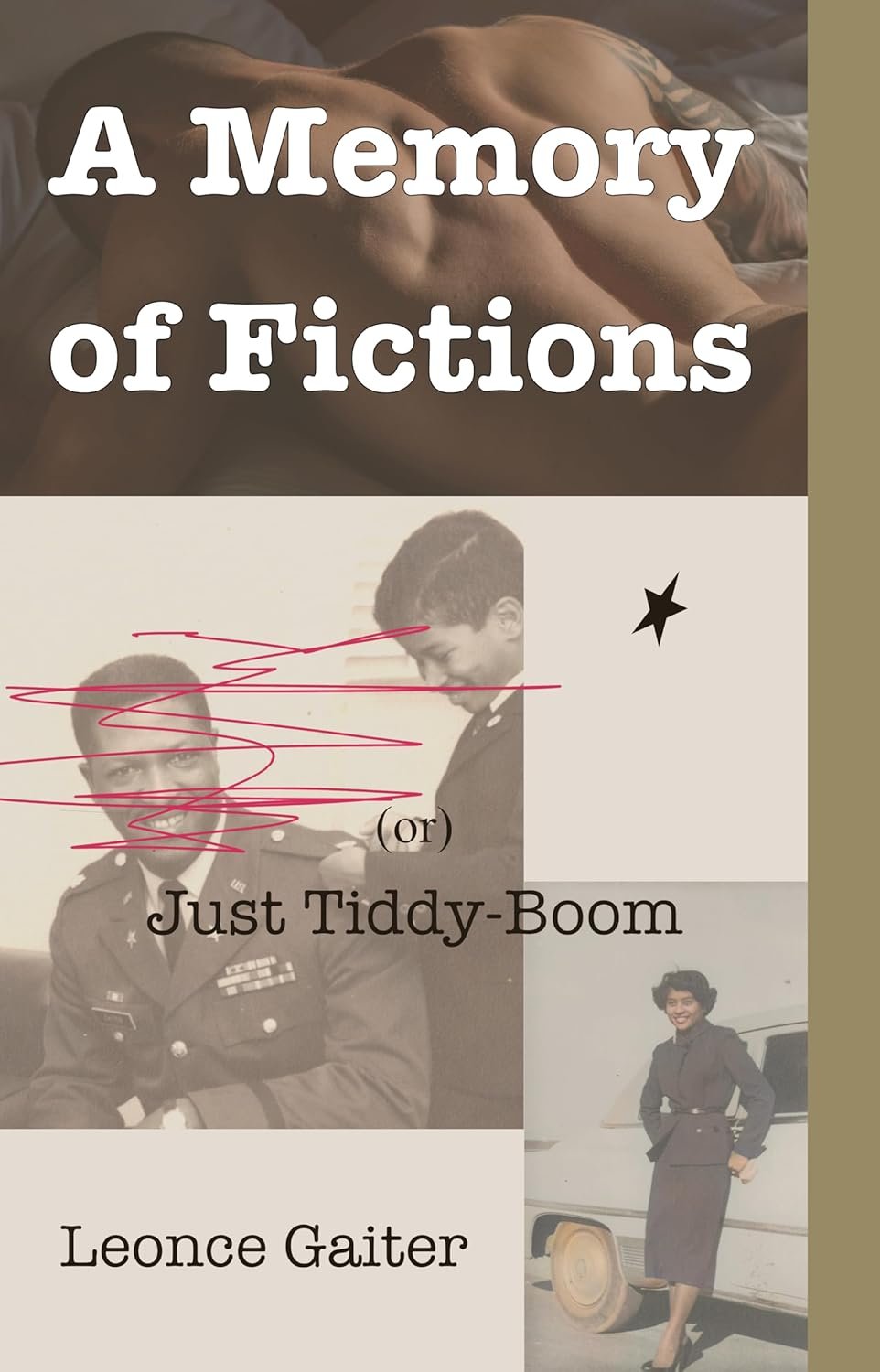

With his latest release, “A Memory of Fictions (or) Just Tiddy-Boom, a lyrical blend of memoir and fiction, Gaiter has once again proven why he is celebrated as a risk-taker in contemporary literature. His work challenges genre conventions, embraces emotional and cultural nuance, and captivates readers with stories that simultaneously transport and provoke. Whether tracing the ragged jazz-like rhythms of a young man’s coming of age or peeling back the layers of New Orleans’s atmospheric allure, Gaiter effortlessly immerses his audience in worlds as dangerous as they are beautiful. In this issue of Reader’s House, we sit down with the award-winning author to delve into his creative process, his literary influences, and his unflinching exploration of the human condition. It is a conversation not to be missed.

How has your upbringing as an “army brat” influenced your writing style and the themes you explore in your books?

Rootlessness is the word the comes to mind. For me, moving often from place to place instilled a sense of instability, and moving from place to place as a black family in the 60s meant anxiety. You never knew what kind of reception you’d receive at a new school as an individual, or, in many cases, as a black one. My characters are often trying to make environments safe for themselves, trying to construct a home, using the only tools they’ve been taught—tools that include violence.

There’s also the question of authority: I’m generally against it, and I’m only half kidding. Son of a military man with a very military mindset, my own bent runs toward exploration and constant questioning. I always chafed at “that’s the way it is,” responses. My characters tend to do the same. My New Orleans southern roots instilled a sense of the gothic and overripe, so I write larger than life characters often in life and death situations, and most of them are trying to rewrite the worlds they live in, upend the established order, often to create world they’re comfortable calling home.

Your novel A Memory of Fictions (or) Just Tiddy-Boom has been described as both lyrical and bold—how did you approach blending memoir and fiction in this work?

Several times I’ve recalled an event to my sibling who has then shared a radically different reading of the same event. We filter our memories through our emotions, prejudices, and other factors we can’t even identify. I knew anything I wrote that touched on events in my own life would be inaccurate, so I leaned into that and used some events in my life as a foundation for an intimate, yet expansive tale that traces the personal, intellectual, and sexual coming of age of young man from the civil rights ‘60s through the Reagan ‘80s.

I am a jazz fanatic and this book in particular references that obsession. Jazz is so exciting because it’s dangerous. It’s held together by sheer talent and with a lapse the whole thing could fall apart. It’s unpredictable, and it is emotionally kaleidoscopic. There is no one “tone” in jazz, or in much of African American music. It can be sad one second, ironic the next, and mocking right after that. I think this book is called “bold” because it, too, is emotionally and structurally kaleidoscopic.

Bourbon Street is deeply rooted in the atmosphere of New Orleans—how did you capture the city’s essence, and what role does setting play in your storytelling?

The time I spent in New Orleans is particularly vivid for me, and not necessarily for good reasons. I took that sense of place from my young memories and built the story around it. “Bourbon Street” is my love letter to film noir, and novelists like Jim Thompson and Patricia Highsmith. Setting in my books is always an outgrowth of character. You might say my characters project the world around them. The characters and the world they inhabit reflect and feed off each other.

Your work often delves into themes of race, identity, and societal expectations—how do you balance historical accuracy with creative storytelling in your historical novels?

When I read historical fiction, I am rarely impressed with writers’ showing off their research. I’m more drawn to a distinct sense of cultural and emotional place within that timeframe. What is this author’s vision of the old west, or Edwardian England? As with memory, historical information will always be filtered through our personal lenses. In historical fiction, I write to immerse you in my take on that period as reflected through characters. I’m less interested in the objective temporal details.

And I don’t think I deal with “identity” per se. I think my characters exist within their identities. There’s a difference. When I write black characters, I don’t write about them being black, which is one definition of writing from a white frame. I write characters who are black. And those black characters assume power. They take for granted they have the power to alter the world around them, and they act to do so with the same sense of righteousness that any white person would.

You’ve worked in film, music, and tech—how have these experiences shaped your approach to writing and storytelling?

I sincerely hope working adjacent to tech has not influenced me in any way whatsoever. With respect to film, I’ve been told my work is very cinematic, but strangely unfilmable. I think the world-building of film—particularly classical Hollywood films—really influenced me, but I project that influence through the writing style. I guess that’s the unfilmable part.

What do you hope readers take away from your exploration of complex characters and morally ambiguous narratives?

First, I hope readers are entertained. I hope they see worlds they’re not accustomed to, peopled with fascinating characters who live in accord with this new world. I hope they take from my work the memory of unique characters sprayed on a larger-than-life canvas.

EDITOR’S CHOICE

A daring, lyrical masterpiece—Gaiter’s voice is unforgettable, weaving raw honesty and poetic brilliance into a fiercely original narrative.