From Ireland to Australia: A Journey of Self-Discovery

Kevin O’Sullivan discusses his literary journey, from A Good Boy to Cheaper than Therapy, sharing insights on storytelling, psychology, resilience, and the power of reclaiming one’s narrative through writing.

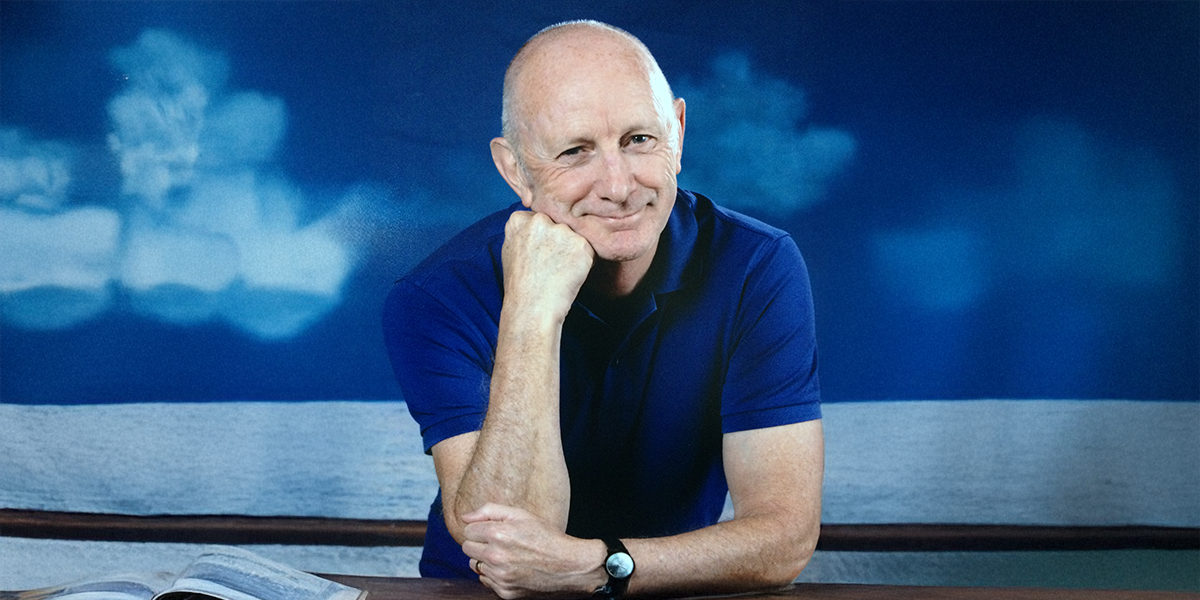

Kevin O’Sullivan is a writer of remarkable depth and honesty, a storyteller who weaves together personal history, psychological insight, and an unflinching curiosity about the human experience. His work spans poetry, memoir, and fiction, each piece infused with a profound understanding of the resilience of the human spirit. Born and raised in Ireland, Kevin’s journey has taken him across continents—from the strict confines of a religious order to the liberating landscapes of Australia, where he now calls home.

His memoir A Good Boy (Atelier Books, 2022) is an extraordinary account of survival, self-discovery, and the courage to break free from an oppressive past. In it, he recounts his early years in the Legionaries of Christ and his eventual escape, a story that is both deeply personal and universally resonant. His forthcoming second volume, Cheaper than Therapy, promises to be just as compelling, chronicling the formative years that shaped his path as a psychologist and writer.

Beyond his literary pursuits, Kevin has spent decades as a clinical and forensic psychologist, bringing the same depth of empathy and understanding to his therapeutic work as he does to his writing. His insight into the human psyche, shaped by both personal trials and professional expertise, makes his reflections on belief, resilience, and identity especially compelling.

In this exclusive interview with Reader’s House, Kevin O’Sullivan discusses the inspirations behind his writing, the challenges of sharing deeply personal experiences, and the profound impact of storytelling. His words remind us of the power of literature not only to recount life but to reshape it—offering understanding, healing, and, ultimately, the ability to reclaim one’s own narrative.

Kevin O’Sullivan is a gifted storyteller whose deeply personal writing illuminates human resilience, psychological depth, and the art of self-discovery.

Why do you write?

I write because I feel the need to write, just like some might feel the need to exercise or talk to friends or go to the movies. It’s as simple as that. Writing is an activity that doesn’t seem to need justifying in my life. I’m fascinated by story, always have been since I was a teenager. I remember at about the age of thirteen, looking at people standing in a bus queue and realising that if you stopped and asked any of them about their life, there would be a story that mattered to them. That fascinates me.

What led you to write a memoir?

I know very little about the past of my family, I didn’t ever meet my father, and by the time I was middle-aged, and realised how little I knew, and thought I would like to know more, it was too late; all the people I could have asked were dead and their stories, by and large, died with them. It is extraordinarily difficult to reconstruct the lives of ‘little people’, people who have no special place in the public record. I didn’t want that to happen to my life. I wanted to write so that if anyone, like my daughter or my nieces and nephews, wanted to know, there would be a source for them.

A Good Boy is a very personal book. How important was it to write like that?

The act of writing makes you an author, the author of the story. If someone else writes it, it becomes their version of you and your story; someone else gets to say who you are. It’s not that my version is in some way more truthful or accurate than someone else’s, it’s just that it’s mine. The story I tell you about myself has at least two components. One is the events that I present, the other is the fact that I choose these events and omit others. I construct myself in writing. Writing is a way of retaining power over your ‘self’.

How did your time in the Legionaries of Christ influence your approach to therapy?

It influenced my approach to people first of all. One of the things I realised about people is that we are capable of believing the most extraordinary things. During my time as a religious, I held what I would now see as quite bizarre beliefs, and I know, at the same time, that I’m a person of goodwill and reasonably intelligent. So that shows me that people who believe things that appear strange to me, are not weird because of that. There’s some understandable basis for their belief. In my work I come across many people who say and do and believe unusual things. Rather than dismissing that, which is easy to do, the first thing I have to do is to work hard at understanding why those beliefs or actions might be important, and to do that respectfully.

You have described the Legionaries of Christ as sect-like. What insights did you take from that experience?

I had first hand experience of seeing a corporate narcissist at work, with the additional element of religious belief thrown in. I think I came away with a greater understanding of how ordinary people fall under the thrall of a charismatic leader (which is a kind way of describing some corporate narcissists!). They can have great charm, by which they invite you into an inner circle of those who ‘know’, who are in some way ‘initiated’. They have utter conviction in the message they’re spreading, and if you repeat something enough times with enough certainty, some perfectly sensible people will begin to think, ‘I wonder if they have a point?‘ You can see this right now in various parts of our world where people are being fed crazy distortions and lies.

What challenges did you face in sharing such personal experiences publicly?

Good question. As I wrote, there were some things I thought that I would cull, things that were hard to write. Believe it or not, I’m a very private person! But the work that I do often involves bringing into the light things that have been hidden through shame or hurt, and by bringing them into the light they’re exorcised, they lose their capacity to harm. If that’s what I do in my work with clients, wouldn’t it be hypocritical not to do it myself? A number of clients have asked me if it’s okay to read A Good Boy because they’re sensitive to an embarrassment I might feel, and I appreciate their care. But the story of one’s life is not that one has made mistakes, the story is that one has survived making those mistakes.

What motivated you to transition from religious life to a career in clinical and forensic psychology?

The motivation for the two is pretty similar. I was sixteen when I went off to join the Legion. I wanted to help, to improve things, to leave things better than I found them, to contribute. I could say all of those things about my work as a therapist. I don’t have a romantic notion of making everything better. I’m well aware that there are some situations you can’t do much about, you just have to endure, and sometimes all I can do is to stand with someone as they endure. And, you know, human beings have an extraordinary capacity to endure. In the next volume of the memoir, which is coming out this year, I go into this transition in more detail.

Tell us a bit about the next volume

The working title is Cheaper than Therapy because it continues the process begun in A Good Boy of constructing a coherent narrative about my life; it’s been my personal therapeutic journey. In some ways it was harder to write than A Good Boy because it surveys the period when I tried to not be ‘a good boy’ and kicked over the traces a bit. I’ve subtitled it How to make mistakes, because it’s a kind of catalogue of fumblings, cul de sacs, gaffes and lots of tears before bedtime.

What advice would you offer to authors aiming to authentically describe their personal experiences?

Have a think about what you want the rest of the world to know about you. Are there risks in self-revelation? Is it the time now? Later? Write the story anyway, warts and all, and then you can decide what you want to share. Also, think, ‘What’s the point of sharing this?’ ‘What might a reader take away that would be of benefit?’ Consider whether you want to sell lots of books or set down your story. Unless you’re already famous, or you have an extraordinary talent and a publisher that spots it, you can say goodbye to buying a beach house with the royalties. My hero in publishing matters is Gabriel García Márquez who sent A Hundred Years of Solitude to twenty-six publishers before he convinced one to take it. And then he won the Nobel Prize!