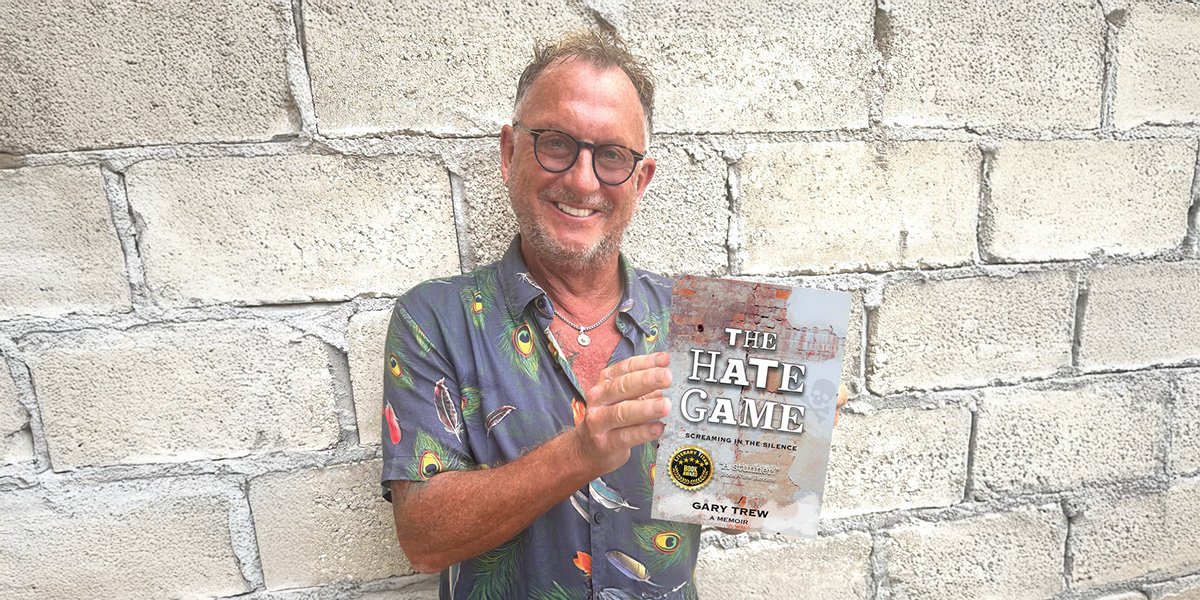

PHOTO: Gary Trew, award-winning author and “that funny British guy,” whose writing turns pain into perspective and darkness into laughter.

Finding Light Through Darkness in Memoir and Crime Fiction

Gary Trew reflects on trauma, resilience, and the unexpected joys of survival through laughter, writing, and personal transformation in his candid and compelling memoir and fiction.

Gary Trew has worn many hats—police officer, minister, child protection social worker—and behind each role is a story both moving and laced with sharp humour. Known affectionately as “that funny British guy” in his adopted home of Canada, Gary brings a unique blend of insight, wit, and humanity to the page. His ability to find absurdity amid adversity has earned him literary acclaim and a loyal readership, particularly with his award-winning memoir The Hate Game: Screaming in the Silence and his darkly comic crime novels under the pen name Denny Darke. In this candid conversation, Gary opens up about trauma, resilience, and the healing power of humour. From the painful realities of schoolyard bullying to the unexpected blessings of meningitis, he offers a powerful testament to the strength found in vulnerability—and the surprising places laughter can take us.

Trew’s voice is fearless, heartfelt, and deeply human—an unforgettable blend of raw honesty and wry humour that leaves a lasting impact.

How did your experiences as a child protection social worker, and police officer shape your perspective on resilience and human nature?

In my early working years, Nietzsche’s saying, “What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger,” became my guiding principle as I saw life’s pain as something to be embraced and endured. However, it wasn’t until I worked in a facility for at-risk youth that I began to view this belief as problematic. I learned that trauma, abuse, and neglect can cause lasting damage to individuals. Past stressors increase the likelihood of developing future mental health issues. Therefore, addressing adverse childhood experiences became crucial for helping children heal and thrive. Through this process, I began to make sense of my own experiences with trauma, which have helped me and others to heal, grow, and develop a healthier outlook on life.

Your memoir details brutal bullying and trauma—was there a particular moment that made you decide to write your story, and was it difficult to revisit those memories?

For many years, I tucked my past experiences away in the back of my mind. As a social worker, I encountered a young person facing similar challenges, which sparked a “Eureka” moment for me: I realised that I had never truly confronted my own trauma. It became apparent that it was time to face my demons, and what better way to do that than by writing a memoir? Revisiting the painful memories of bullying and abuse was difficult because of the guilt and shame I carried. To gain perspective, I reached out to former classmates who validated my experiences and shared their own shocking stories. I knew that this would mean reopening old wounds. I expected to receive praise from some people but also anticipated criticism from others, primarily since some former students viewed their time at Knoll as the best years of their lives.

Humour plays a big role in your writing despite the dark themes—how do you balance the pain and laughter in your storytelling?

Humour has long been my way of coping with stressful situations. At school, students facing bullying often use humour to navigate their harsh experiences and bond with peers. It provided a sense of control in circumstances where we felt powerless. Reporting bullying was futile, as some staff members were even worse than the students, so we would act out in class and share laughter. I remember facing the toughest student in school and laughing afterwards at how surreal it was. While there are moments for seriousness, humour also has its place, and storytellers need to consider their audience, as what amuses one person may not resonate with another.

You mention that meningitis had unexpected effects, like improving your coordination and taste preferences—how do you view these changes now, and have they influenced your approach to life?

Meningitis was both a blessing and a curse. Initially, learning became a massive issue for me. I didn’t understand why I suddenly sucked at chemistry and pharmacology at university. Before I got sick, learning was easy for me. After meningitis, I adapted my approach and tapped into my creative side. I colour-coded everything and built 3-D models of atomic structures with Lego pieces. While it took longer to understand concepts, I became a unique “think outside the box” problem solver. When I write my fiction work, I envision a multicoloured movie scene unfolding before my eyes. It’s very cool. In an unexpected twist, meningitis has become a remarkable blessing in my life.

You’ve led a life filled with transformation, from overcoming dyslexia to gaining multiple degrees—what advice would you give to someone facing similar challenges?

I faced many obstacles before returning to university later in life. After being rejected from the UVIC BSW (social work) program, I reapplied the next year with improved grades from supplementary courses. The same Registrar warned that I might struggle and reluctantly accepted me. I graduated with top marks and an impressive GPA—the Registrar was stunned. Gary, the old man, did it! Therefore, follow your passion, don’t give up, and embrace failures and messing up as opportunities for growth.

What was the biggest challenge in writing The Hate Game, and did the process of writing it bring any unexpected personal revelations?

Overcoming guilt and shame was a significant journey for me—I hadn’t shared that I had been sexually assaulted, but I felt it was important to include this experience in my narrative. My biggest challenge was battling imposter syndrome, which caused me to doubt my identity and writing abilities. My editor, a creative writing professor, helped me silence the imposter. She said, “If you were one of my students, I would give you a clear distinction. This is some of the best debut writing I’ve seen.”

Your memoir highlights the cruelty of school bullying in the 1970s—do you think things have changed for children today, or do similar patterns still exist in different forms?

The introduction of the National Curriculum, increased parental choices, and improved teacher training have enhanced the education system. At The Knoll, body shaming, homophobia, and physical abuse were prevalent. Nowadays, few schools would tolerate students drawing swastikas on pupils’ foreheads or playing playground ‘gas chambers,’ never mind immersing them in toilet water and urine. Teachers ignored this behaviour—unacceptable today. Reporting misconduct was taboo. However, today’s youth are more open about their feelings. While awareness and prevention efforts have reduced bullying, new forms, such as cyber and social bullying, are negatively impacting children.

What advice would you offer to other authors looking to write deeply personal and emotionally challenging memoirs?

I penned this memoir to illuminate my journey of perseverance amid profound adversity, unveiling the unexpected moments of joy I found along the way. It’s crucial not to write from a place of anger or revenge. I began to understand generational trauma and the reasons behind family members’ behaviours. So, be honest and focus on your personal growth. Reading other memoirs is essential for your journey as a memoir writer. It helps you connect with others, find inspiration, and appreciate the power of personal storytelling. “The Glass Castle” and “Angela’s Ashes” inspired me. Westover’s “Educated” shares similar yet different experiences, while David Sedaris’s “Talk Pretty” memoir is darkly hilarious. Recalling trauma can be difficult, and it’s important to understand that hurt people often hurt others. Remember, writing this kind of memoir is not merely about reliving pain and misery—it’s about personal transformation, healing and growth.

“I began to understand generational trauma and the reasons behind family members’ behaviours.”- Gary Trew