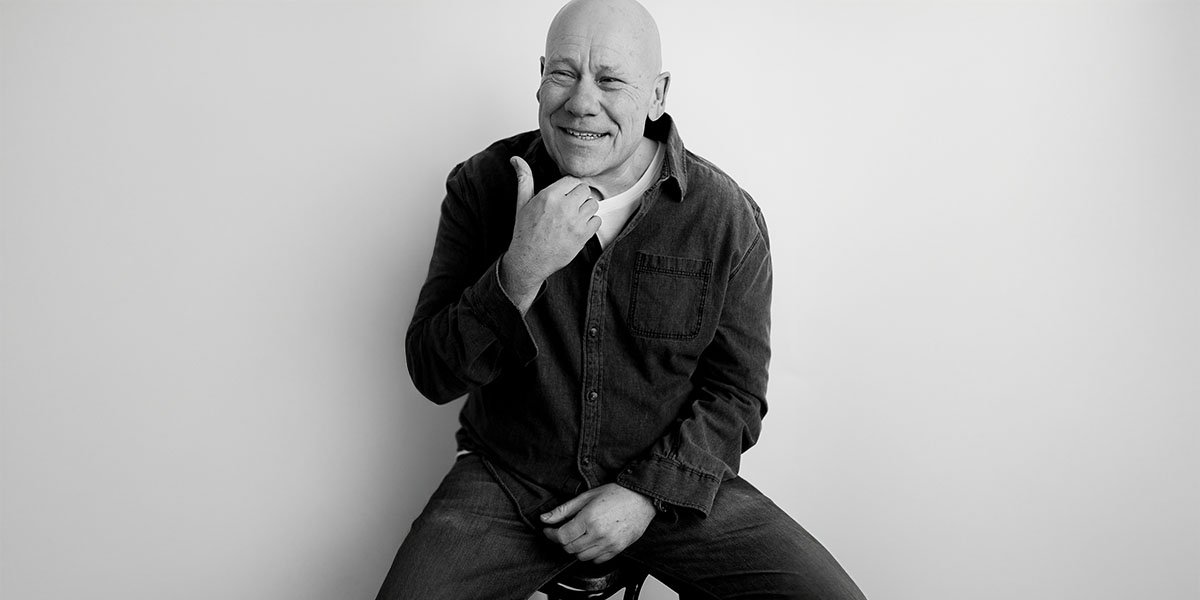

PHOTO: Robert Jenkins, author of acclaimed novel The Fell, whose life and stories shine a light into unseen worlds.

From London’s Marshes To Literary Acclaim

Robert Jenkins reflects on his gritty East London roots, the transformative power of storytelling, and how his life experiences have shaped works like The Fell and The Skinny Man.

Robert Jenkins has always had a singular gift: the ability to find poetry in the raw edges of life. Born amidst the marshes of East London, his formative years were shaped by the rugged beauty of Hackney’s waterways and the vibrant, often chaotic gypsy community around him. From these beginnings, he crafted a voice both unyielding and tender, one that champions the imperfect defiance of those striving against the odds. His writing is neither sentimental nor detached—it dwells in the messy complexities of human nature, reflecting lives caught between survival and transcendence.

What sets Jenkins apart as a contemporary literary craftsman is his versatility. From plays and film scripts to his acclaimed novel The Fell, his work carries the weight of memory while celebrating the possibilities of imagination. He affords deep respect to his characters—even when flawed, even when broken—imbuing them with life and dignity. The Fell’s “urban tribe,” as one critic noted, pulses with rebellion and loss, yet bursts with moments of unexpected humour and triumph. It’s an authenticity born from a writer who lived among marginalised communities, steered the chaos of young offenders, and grappled with the delicate tensions of mentorship and belonging.

His short story The Skinny Man, which won New Zealand’s Sunday Star-Times award, is further proof of Jenkins’ mastery of form and meaning. Within its concise framework, he unpacks the novelistic depth of Coppermill Lane, transforming memory into metaphor with precision. Jenkins doesn’t merely write—he excavates, peeling back the layers of history and emotion to reveal truths often hidden in plain sight. There is a fearless honesty to his craft that renders his words both beautiful and uncompromising, a reminder that fiction need not be divorced from the real. In his hands, it can be both—and therein lies its power.

Robert Jenkins has a unique talent for crafting raw, authentic narratives filled with beauty, humanity, and uncompromising honesty.

In “The Fell,” how did your upbringing in East London influence the novel’s setting and characters?

I think the influence of upbringing and environment is always present. Sometimes the memories and influences are buried, but writing uncovers them. I’m not even sure what is imagined and what is remembered, but growing up in a densely populated inner-city area definitely provided material I later wrote into The Fell. Not all fiction is all fiction!

What inspired the creation of Feallan House, and is it based on any real institutions?

Some years ago I ran a boarding house for up to 100 teenage boys aged from 13-19. I lived-in with five other adults. It was 24/7 immersion. I was approached by the governors who said that the boys and staff were at war and the boys had won… I went to look at the place and it was like a Soviet-era asylum, filled with kids who looked like the cast of a dystopian Lord of the Flies remake. I couldn’t resist it.

“I’m not even sure what is imagined and what is remembered, but growing up in East London shaped everything.” – Robert Jenkins

How did your experiences working with marginalised individuals shape the themes in your writing?

The people and environment we are immersed in, shapes everything. We can smooth over some of it, build on it, gild it, but when I write, I try to write honestly. Just because it’s a work of fiction doesn’t mean it isn’t very real and I have to be able to defend my characters. If I cheat them, they punish me. The Fell is a smorgasbord, an authentic reflection of challenged people in challenging circumstances, struggling and somehow pulling each day into shape, and not quite understanding the world or their place in it but trying to make sense of it all. You see that every day in the people around you. A kind of imperfect defiance.

“The Skinny Man” won the Sunday Star-Times Short Story Award; what was the genesis of this story?

The Skinny Man was initially written as part of my latest novel, Coppermill Lane (seeking a publisher). The bulk of it forms Chapter 6! While I was editing Coppermill Lane (still seeking a publisher), I thought the chapter could work as a standalone short story, so I honed it down. The place was real, as was the man. I didn’t know that until I was writing it.

Your prose has been compared to Steinbeck and Salinger; which authors have most influenced your style?

That’s some compliment! Say it again!

“Not all fiction is all fiction!” – Robert Jenkins

I think Steinbeck influenced me very young. I lived close to a large library and went there often. It was a doorway into so many worlds. A lifesaver. I recall aged about 13 reading the preface page of Cannery Row and instantly falling in love with literature. It was the first time I’d ever read about a place akin to where I lived, described not as a slum but a paradise and the people written not as victims and paupers but poets and princes. Choose your lens!

Afterwards, I read everything I could get my hands on and of course everything had some level of influence or impact. Toni Morrison wrote terrible themes with a beauty that made me feel guilty admiring it. William Blake, Shakespeare, Conrad, Hemingway, McCarthy, Faulkner. The list goes on. Sometimes what is written influences, but more often, how it is written. I deconstruct a lot.

How do you balance the rawness of adolescence with poetic language in your narratives?

Rawness and poetry go together. Raw doesn’t have to mean base. It’s just unshaped, maybe more natural. I like that. Accept that, and poets are everywhere!

“I try to write honestly. Just because it’s a work of fiction doesn’t mean it isn’t very real.” – Robert Jenkins

Also as a writer it’s important to develop an ear for the spoken word. Hearing a turn of phrase, an unexpected word or non-word in a sentence that might be considered ‘wrong’ and yet works perfectly. That’s the beauty of English. People naturally understand the meter and rhythm of words. Go with it.

What challenges did you face when transitioning from short stories to writing a full-length novel?

For me it’s the other way around. Writing a novel you have so much more leeway, so much more room. It’s the cutting that kills you! The Fell took seven or eight drafts to get tight and with hindsight could use one more… The Skinny Man was worked down to 3000 words from 6000… and losing the last twenty words took me a month. The last five, took weeks. It’s tight writing where we bleed, but it’s non-negotiable. It’s craft.

What advice would you offer aspiring authors striving to find their unique voice?

Keep listening, you’ll hear many voices, then the one… and talk to it (not out loud…). Hear it speak back to you (don’t do what it says…). Hear its story. Let it grow and take its shape. Let it live. Don’t sanitise it. Let it possess you. Trust it. See its world. Show it yours. Write what moves you, what haunts your dreams. Stay honest. And write for just one reader (not your mum or Aunt Mavis), and direct everything to them.

Finally, when the voice rants and rambles, be brutal. Cut, cut and cut.