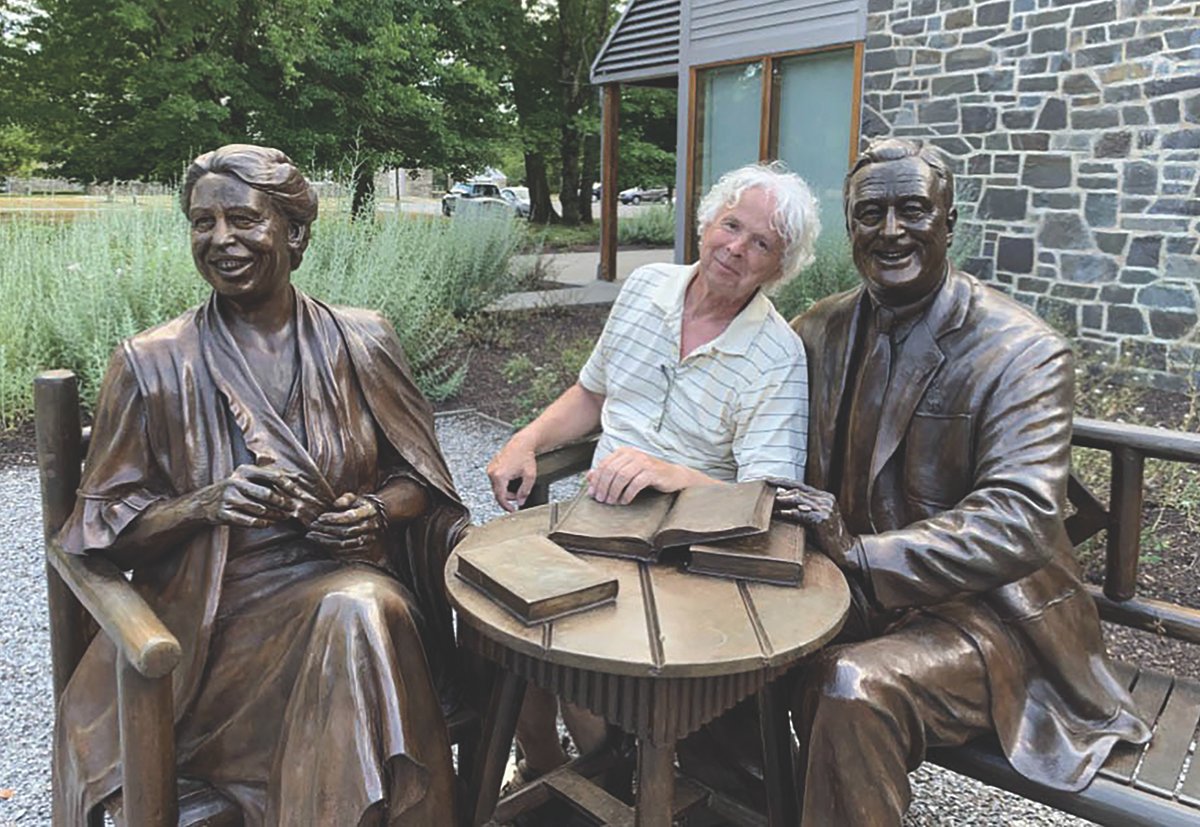

Photo: Author Daniel Hayes enjoying an afternoon visit with bronze friends and fellow New Yorkers Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt at their home in Hyde Park, New York. Renowned for his masterful storytelling, Hayes––whose works such as The Trouble with Lemons and Flyers resonate deeply with young adults––manages to blend whimsical humour with the poignant complexities of life.

Daniel Hayes On Writing, Teaching, And Aspirations For Film

Daniel Hayes reflects on growing up in rural New York, his teaching inspiration, his vivid characters, blending humour with serious themes, and the journey of adapting novels to film.

Daniel Hayes is an author who embodies the essence of storytelling with heart, humour, and an uncanny ability to capture the pulse of adolescence. A man deeply rooted in his heritage, Hayes has taken the intricate threads of his upbringing in rural Upstate New York and woven them into rich fictional worlds that resonate with readers from all walks of life. From the tender dynamics of family in Flyers, to the sharp and relatable insights of teenage life in The Trouble with Lemons, Hayes’s works are not only masterpieces of young adult literature but also universal explorations of identity, loss, and self-discovery.

As both an accomplished educator and a skilful writer, Hayes brings to his stories a unique vibrancy informed by over four decades of teaching English and Creative Writing. His ability to seamlessly bridge the gap between humour and poignancy truly sets him apart, and his characters—such as the unforgettable Tyler and Lymie—leap off the page with a realism that feels astonishingly genuine. Hayes’s narratives are alive with wit, authenticity, and an underlying humanity that captures the intricacies of life’s joys and tribulations.

With four critically acclaimed novels under his belt and his fifth, My Kind of Crazy, in the works, Hayes’s literary star continues to rise, as does his ambition to extend his storytelling into the realms of film and television. Readers familiar with his works will undoubtedly share his excitement at the prospect of seeing his vivid characters brought to life on screen. Hayes’s devotion to his craft, paired with his keen philosophical insights, makes him an author whose words leave an indelible mark—engaging minds and touching hearts in equal measure.

In this issue of Reader’s House, we are thrilled to present an illuminating interview with Daniel Hayes. Join us as he delves into the inspirations behind his stories, reflects on his career, and opens up about his aspirations, writing process, and personal experiences. Hayes’s insights remind us of the magic that lies at the heart of storytelling and the timeless appeal of a tale well told. This is an author who invites us to think, laugh, and feel deeply—a master of his craft, and a voice that continues to enrich the literary landscape with wisdom and wit.

Daniel Hayes is a masterful storyteller, brilliantly capturing the complexities of adolescence and life with authenticity, heart, and humour.

What inspired you to base the fictional village of Wakefield on your hometown of Greenwich, New York?

I grew up on a dairy farm outside the village of Greenwich (which we stubbornly pronounce Green Witch!), and although I loved living in the country with plenty of land to explore, trees to climb, and ponds to swim in, I envied the village kids, at least somewhat, for being in the midst of what my childhood self considered “all the action.” The water-filled rock quarry featured in The Trouble with Lemons was on the outskirts of the village and represented to many of us a forbidden and vaguely mysterious place, so of course we all wanted to sneak there whenever we could. When I read a story many years later of a body of a young man turning up in a similar quarry in the Midwest, I had the idea to create and deposit a corpse into a fictional Wakefield version of our own very real quarry, and this became the start of my first novel.

How has your experience as a high school English teacher influenced the way you write for young adults?

Teaching junior high and high school for all those (45+) years kept me in touch, I think, with the attitudes and concerns of the coming-of-age generations. Styles change over the years, of course, and popular expressions and hip terms come and go, but a generic “kidness” always seems to remain. The world is an exciting (although often daunting) place for the young. Problems and concerns are often amplified at that age, but so too are the hopes and dreams and the exhilarating sense of adventure in exploring the world. Being surrounded by young people also served as a reminder of the kid that was still in me.

Tyler and Lymie are such vivid, believable characters—are they based on people you’ve known or entirely from your imagination?

Tyler’s voice, I think, was largely my own, or at least a younger version of it, and Lymie was a compilation of friends I grew up with. Tyler’s feeling of vulnerability expressed through his inner dialogue contrasts with Lymie’s seemingly more straightforward approach to life. Part of this distinction may be that we’re able to enter Tyler’s head through his first person narration whereas we can only see Lymie from his overt reactions and words. Having Tyler and Lymie appear as foils to each other highlights each of their personalities and adds, ironically, to their camaraderie.

Your books often blend humour with serious themes like grief and identity. How do you strike that balance in your writing?

Each of our lives is a mixture of all these elements, and in order for fiction to be realistic it must contain all these themes. The way each writer mixes these, however, is unique and based on his or her personality, experiences, and writing style. I tend to see at least a little humor in even the most difficult experiences, both in my own life and in my writing.

Can you tell us more about your aspirations to see your novels adapted into films?

I’ve been waiting a long time for this to happen, haha! Way back in 1991 when my first novel The Trouble with Lemons received a blessedly positive review in Publishers Weekly, Steven Spielberg’s agent called my agent requesting that a copy of the book be sent over. I’ve been waiting on the edge of my seat ever since. We’ve had a number of serious nibbles over the years, including one from Steve Waterman who wanted to do a feature film on Flyers, and Bo Zenga who saw potential for a TV or film production of the Tyler/Lymie series, but, alas, so far nothing has quite come to fruition. Being the eternal optimist, I haven’t given up, though, and believe that when the time is right, something will happen.

In Flyers, you explore some deep family themes. How personal was that story for you?

Most stories are, in obvious or sometimes not so obvious ways, influenced by personal experiences, and mine are no exception. Having seen firsthand, for instance, the varying effects that alcoholism and other forms of less than perfect parenting can have on families, I wanted to portray the family dynamics of Gabe’s family in Flyers with as much nuance as possible. Pop has what most people would consider to be a pretty serious drinking problem, but he’s also undeniably a devoted and loving father who is adored by his two sons. One could argue that since the sons don’t devolve into victimhood and self pity, they are growing into stronger human beings who will be ready to deal with all the complexities they’ll undoubtedly have to face in the world. In contrast to this, I have what I hope is some good-natured fun with Bob Chirillo, the social worker, first seen in No Effect and then in Flyers, who, in his zeal to uncover problems he can swoop in to cure, is compared to a fireman who likes fires a little too much. Having been, actually, a volunteer fireman as a young man, I remember that feeling of vague disappointment upon arriving at a call eager to pitch in and save the day only to find that the fire had already been extinguished. Human nature is a funny thing; we can either berate ourselves for succumbing to our human frailties or see the humor in them and go forward as best we can.

What has been the most memorable reaction you’ve had from one of your novels?

I once received a letter (back in the day when people sent letters) from a young man who told me that Flyers had changed his life profoundly and had given him a whole new perspective on life and death. My first reaction was that this letter had been written by one of my jokester students, who would often tease me about my tendency to philosophize about such subjects in our discussions of life and literature. In fact, I almost answered it by saying something to the effect of “Haha! Did you really think I’d be dumb enough to fall for this?!!!” I hesitated, though, noting that the letter had come from the American Midwest and my jokester students and I were planted in Upstate New York. Fortunately, despite the risk of falling prey to a practical joke, I responded to the letter with sincere gratitude and appreciation along with some background information about the death scene, which was similar to what I had experienced at the death of my father. The letter turned out to be genuine and it remains one of the most moving letters I’ve received from a reader. Plus, I was able to share what I considered to be a funny story with my students, some of whom still laugh about how I came close to responding with a How-stupid-do-you-think-I-am response, one which I have to think would have been somewhat disconcerting (and maybe even a little traumatizing) to a thoughtful reader trying to express his sincere appreciation to an author whose book had meant something important to him.

What advice would you give to other authors trying to capture authentic teenage voices and experiences in their work?

Having sat through way too many earnest and well-intentioned graduation speakers, often students themselves dispensing life lessons to their fellow graduates, and being aware that my own life is still very much a work in progress, I try to reign myself in when I feel the need to pontificate on any subject, all too often with limited success. So with abject apologies, here I go again: Writers (especially those who write for the young) must resist the temptation to make their stories teaching tools. A good story will present dilemmas and choices which often reflect the writer’s worldview, but using stories to present “lessons” in life from one who is older and feels wiser can greatly reduce their power. Mark Twain, one of my all-time favorite writers, spoofed this moralizing directly in “Story of the Bad Little Boy,” featuring a main character who did everything “wrong” and, against all the unspoken dictates of children’s literature of that era, happily received the benefits of his wrongdoing, getting away scotfree and fulfilled. Twain played with this theme a little more indirectly in The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, whose titular character rose above contemporary morals, choosing instead to rely on his own moral compass. This heresy resulted in Huck Finn being, not merely criticised, but outright banned from many schools and libraries. The best stories, I feel, are always at least a little subversive to the status quo, and without authors being willing to challenge the accepted beliefs of the day, society might be a lot less likely to evolve.

Leave a Reply