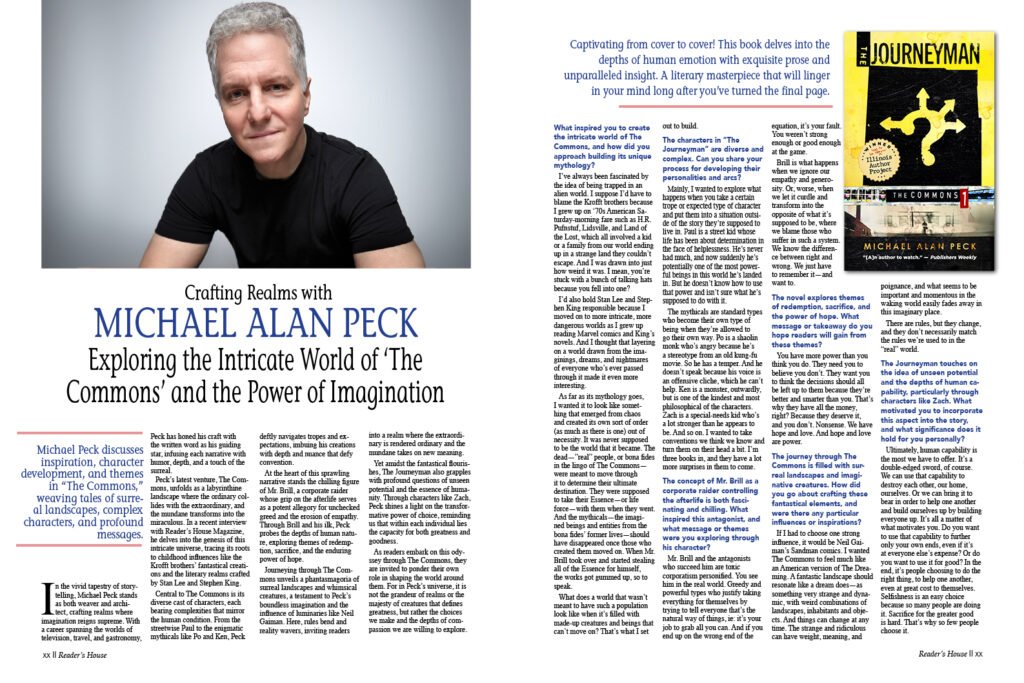

Exploring the Intricate World of ‘The Commons‘ and the Power of Imagination

Michael Peck discusses inspiration, character development, and themes in “The Commons,” weaving tales of surreal landscapes, complex characters, and profound messages.

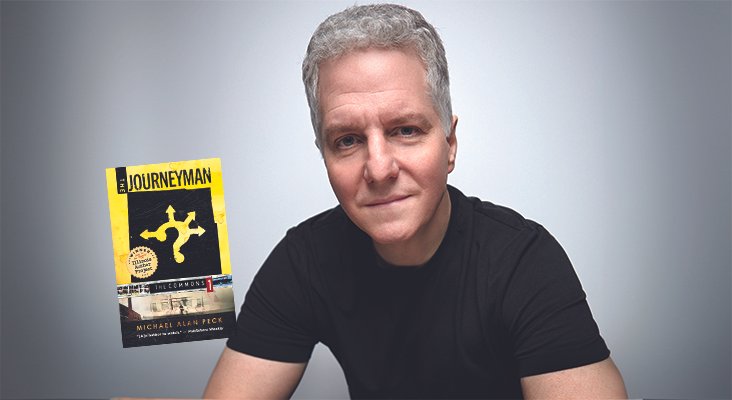

In the vivid tapestry of storytelling, Michael Peck stands as both weaver and architect, crafting realms where imagination reigns supreme. With a career spanning the worlds of television, travel, and gastronomy, Peck has honed his craft with the written word as his guiding star, infusing each narrative with humor, depth, and a touch of the surreal.

Peck’s latest venture, The Commons, unfolds as a labyrinthine landscape where the ordinary collides with the extraordinary, and the mundane transforms into the miraculous. In a recent interview with Reader’s House Magazine, he delves into the genesis of this intricate universe, tracing its roots to childhood influences like the Krofft brothers’ fantastical creations and the literary realms crafted by Stan Lee and Stephen King.

Central to The Commons is its diverse cast of characters, each bearing complexities that mirror the human condition. From the streetwise Paul to the enigmatic mythicals like Po and Ken, Peck deftly navigates tropes and expectations, imbuing his creations with depth and nuance that defy convention.

At the heart of this sprawling narrative stands the chilling figure of Mr. Brill, a corporate raider whose grip on the afterlife serves as a potent allegory for unchecked greed and the erosion of empathy. Through Brill and his ilk, Peck probes the depths of human nature, exploring themes of redemption, sacrifice, and the enduring power of hope.

Journeying through The Commons unveils a phantasmagoria of surreal landscapes and whimsical creatures, a testament to Peck’s boundless imagination and the influence of luminaries like Neil Gaiman. Here, rules bend and reality wavers, inviting readers into a realm where the extraordinary is rendered ordinary and the mundane takes on new meaning.

Yet amidst the fantastical flourishes, The Journeyman also grapples with profound questions of unseen potential and the essence of humanity. Through characters like Zach, Peck shines a light on the transformative power of choice, reminding us that within each individual lies the capacity for both greatness and goodness.

As readers embark on this odyssey through The Commons, they are invited to ponder their own role in shaping the world around them. For in Peck’s universe, it is not the grandeur of realms or the majesty of creatures that defines greatness, but rather the choices we make and the depths of compassion we are willing to explore.

What inspired you to create the intricate world of The Commons, and how did you approach building its unique mythology?

I’ve always been fascinated by the idea of being trapped in an alien world. I suppose I’d have to blame the Krofft brothers because I grew up on ‘70s American Saturday-morning fare such as H.R. Pufnstuf, Lidsville, and Land of the Lost, which all involved a kid or a family from our world ending up in a strange land they couldn’t escape. And I was drawn into just how weird it was. I mean, you’re stuck with a bunch of talking hats because you fell into one?

I’d also hold Stan Lee and Stephen King responsible because I moved on to more intricate, more dangerous worlds as I grew up reading Marvel comics and King’s novels. And I thought that layering on a world drawn from the imaginings, dreams, and nightmares of everyone who’s ever passed through it made it even more interesting.

As far as its mythology goes, I wanted it to look like something that emerged from chaos and created its own sort of order (as much as there is one) out of necessity. It was never supposed to be the world that it became. The dead—”real” people, or bona fides in the lingo of The Commons— were meant to move through it to determine their ultimate destination. They were supposed to take their Essence—or life force—with them when they went. And the mythicals—the imagined beings and entities from the bona fides’ former lives—should have disappeared once those who created them moved on. When Mr. Brill took over and started stealing all of the Essence for himself, the works got gummed up, so to speak.

What does a world that wasn’t meant to have such a population look like when it’s filled with made-up creatures and beings that can’t move on? That’s what I set out to build.

The characters in “The Journeyman” are diverse and complex. Can you share your process for developing their personalities and arcs?

Mainly, I wanted to explore what happens when you take a certain trope or expected type of character and put them into a situation outside of the story they’re supposed to live in. Paul is a street kid whose life has been about determination in the face of helplessness. He’s never had much, and now suddenly he’s potentially one of the most powerful beings in this world he’s landed in. But he doesn’t know how to use that power and isn’t sure what he’s supposed to do with it.

The mythicals are standard types who become their own type of being when they’re allowed to go their own way. Po is a shaolin monk who’s angry because he’s a stereotype from an old kung-fu movie. So he has a temper. And he doesn’t speak because his voice is an offensive cliche, which he can’t help. Ken is a monster, outwardly, but is one of the kindest and most philosophical of the characters. Zach is a special-needs kid who’s a lot stronger than he appears to be. And so on. I wanted to take conventions we think we know and turn them on their head a bit. I’m three books in, and they have a lot more surprises in them to come.

The concept of Mr. Brill as a corporate raider controlling the afterlife is both fascinating and chilling. What inspired this antagonist, and what message or themes were you exploring through his character?

Mr. Brill and the antagonists who succeed him are toxic corporatism personified. You see him in the real world. Greedy and powerful types who justify taking everything for themselves by trying to tell everyone that’s the natural way of things, ie: it’s your job to grab all you can. And if you end up on the wrong end of the equation, it’s your fault. You weren’t strong enough or good enough at the game.

Brill is what happens when we ignore our empathy and generosity. Or, worse, when we let it curdle and transform into the opposite of what it’s supposed to be, where we blame those who suffer in such a system. We know the difference between right and wrong. We just have to remember it—and want to.

The novel explores themes of redemption, sacrifice, and the power of hope. What message or takeaway do you hope readers will gain from these themes?

You have more power than you think you do. They need you to believe you don’t. They want you to think the decisions should all be left up to them because they’re better and smarter than you. That’s why they have all the money, right? Because they deserve it, and you don’t. Nonsense. We have hope and love. And hope and love are power.

The journey through The Commons is filled with surreal landscapes and imaginative creatures. How did you go about crafting these fantastical elements, and were there any particular influences or inspirations?

If I had to choose one strong influence, it would be Neil Gaiman’s Sandman comics. I wanted The Commons to feel much like an American version of The Dreaming. A fantastic landscape should resonate like a dream does—as something very strange and dynamic, with weird combinations of landscapes, inhabitants and objects. And things can change at any time. The strange and ridiculous can have weight, meaning, and poignance, and what seems to be important and momentous in the waking world easily fades away in this imaginary place.

There are rules, but they change, and they don’t necessarily match the rules we’re used to in the “real” world.

The Journeyman touches on the idea of unseen potential and the depths of human capability, particularly through characters like Zach. What motivated you to incorporate this aspect into the story, and what significance does it hold for you personally?

Ultimately, human capability is the most we have to offer. It’s a double-edged sword, of course. We can use that capability to destroy each other, our home, ourselves. Or we can bring it to bear in order to help one another and build ourselves up by building everyone up. It’s all a matter of what motivates you. Do you want to use that capability to further only your own ends, even if it’s at everyone else’s expense? Or do you want to use it for good? In the end, it’s people choosing to do the right thing, to help one another, even at great cost to themselves. Selfishness is an easy choice because so many people are doing it. Sacrifice for the greater good is hard. That’s why so few people choose it.