PHOTO: Don Aker, acclaimed author of young adult fiction, photographed by Nicola Davison of Snickerdoodle Photography.

Writing Truth Hope And Resilience For Young Readers

Don Aker reflects on his journey from teacher to acclaimed author, discussing inspiration, authenticity, and the transformative power of storytelling in shaping young adult voices, resilience, and the search for identity.

Don Aker’s name has become synonymous with powerful storytelling that lingers long after the final page. A former teacher turned full-time writer, he has devoted his career to capturing the turbulence of adolescence with unflinching honesty. His novels—among them The First Stone, The Fifth Rule, Running on Empty, and Delusion Road—grapple with moral complexity, personal struggle, and the fragile hope that can emerge from even the darkest of circumstances.

What sets Aker apart is not merely the subjects he chooses, but the compassion with which he treats them. His young characters stumble, falter, and often fail, yet they are never stripped of their humanity. Whether confronting grief, guilt, or injustice, his protagonists carry within them a raw truth that resonates with readers navigating their own uncertain paths.

It is perhaps unsurprising that Aker’s deep understanding of young people stems from decades spent in the classroom. Those years afforded him not only insight into the challenges and resilience of youth but also a constant source of voices, gestures, and stories that infuse his fiction with authenticity. In every book, one senses the teacher still at work—guiding, questioning, encouraging.

Above all, Aker writes with the conviction that stories matter—that they can reflect, unsettle, and ultimately heal. His narratives rarely promise neat resolutions, yet they always leave space for hope. For young readers, that spark of possibility is perhaps the most enduring gift his work has to offer.

In Delusion Road, you delve into themes of trauma and justice. What inspired you to explore these complex issues through the lens of young adult fiction?

If I were asked to choose between eating a bug or reliving the worst day of my teen years, I’d respond, “How big is the bug?” What draws me to write about young adults is this unique period in their lives characterized byincredible upheaval, rapid change, deep feeling, and the search for identity. At no other timein their liveswill they undergo more challenges in such a brief period, and often when they’reill-equipped to handle them. As a classroom teacher, I have watched far too manymarginalized young peopleendure abuse bythose with power, and that was the impetus for this novel.

“At no other time in their lives will they undergo more challenges in such a brief period.” – Don Aker

Your novel The First Stone addresses the aftermath of a tragic accident. How did real-life events influence the development of Reef’s character and his journey?

The daughter of a friend was killed when a teenager in astolen vehicle struck her car while he was trying to evade police in a high-speed chase. For the longest while, I couldn’t stop thinking about that teenager, and I wondered what had happened in his life thathad shaped him into the sort of person who would run a red light during rush hour surely knowing that, in doing so, some innocent personwould be maimed or killed. In creating Reef, I spent a long time envisioning the types of influences—both human and environmental—that might eventually lead a young man to throw a rock off an overpass into oncoming traffic. I also had to explore how he might react when having to face the tragicconsequences of his action, which led me to spend time observingat a rehabilitation centre and speaking with law enforcement officers. Everything I learned during my research guided my writing of Reef’s journey.

“Real life isn’t tidy… readers have to imagine what happened to Connor after returning home from Mexico.” – Don Aker

The Space Between offers a unique perspective on its characters. Can you discuss the decision to leave certain storylines unresolved, particularly Connor’s fate?

That’s such a good question, especially since so many readers have asked me what eventually became of Connor. To be honest, I have no idea what happened tohim after the events of the novel. As I was working on the final scenes, my writing brain simply had no further use for him. In taking the brave step to come out to Jace but then ultimately choosing to hide from the world who he was, Connor had served his purpose—helping Jace recognize the harm in keeping his own feelings and fears locked down. And at the risk of sounding flippant, real life isn’t tidy. As human beings, we don’t always learn the answers to all of our questions—we’re often forced to imagine how things worked out for people who are no longer part of our lives. In the same way, readers have to imagine what happened to Connor after returning home from Mexico.

Your writing often portrays flawed characters facing personal struggles. How do you ensure these portrayals remain authentic and resonate with young adult readers?

I consider myself very fortunate to have been a teacher for 33 years and, although I’m now retired from the classroom, I get into schools frequently as a visiting author. Speaking to (and shamelessly eavesdropping on) students has provided me with endless opportunities to draw from their experiences when I write. A friend gave me what is now my favourite t-shirt, which reads, “Careful, or you’ll end up in my novel.” Nothing could be truer.

Having transitioned from a classroom teacher to a full-time author, how has your educational background influenced your approach to writing for young adults?

My background as an educator has made me intimately aware of the challenges that many young adults face when they pick up a book. Literacy specialist Kylene Beers once told of asking a struggling student what he saw as he read, and he replied, “One damn word after another.” But reading is far more than simply decoding letters on a page, and my background as a teacher gave me insight into the various processes—visualization being only one of these—that people bring to bear when they attempt to make meaning of text. This understanding has influenced how I structure a story, how I must provide readers with context that will move them forward, and so on.

Scars and Other Stories showcases a collection of short fiction. What challenges did you face in crafting short stories compared to your full-length novels?

My greatest weakness as a novelist is my tendency to overwrite, and I’ve been fortunate to have worked with editors who tell me (in the gentlest of terms) when paragraphs or pages or, in some cases, whole chapters need to be excised from a manuscript. For example, the first suggestion my editor made after reading my draft of Delusion Road was to cut 40,000 words. I did—and vastly improved the novel as a result. Interestingly, I don’t have that problem when I write short stories, probably because the genesis of a novel is invariably an issue while the seed of a short story is always a moment—something I’ve seen or heard or done that resonated with me until I couldn’t help writing about it. British author Victor Pritchett put it best when he said, “A short story is what you see when you look out of the corner of your eye.”

Your works frequently tackle difficult topics such as abuse and identity. What do you hope readers take away from these narratives?

My goal is for readers to come away from my stories with a sense of hope. Not all of my novels or short stories end happily—in fact, the novel that elicited the most fan mail I’ve ever received was The First Stone, and while the vast majority of readers enjoyed the book, many of them hated the way I’d ended it.I believe the happiness of an ending is irrelevant. What counts is how realistically it concludes my main character’s journey. More than anything, I want my readers to have seen themselves in my characters and understand the choices they’ve made, choices that will ultimately move them along their paths to better tomorrows.

What advice would you offer to aspiring authors looking to write compelling stories for young adult audiences?

I would offer aspiring authors three pieces of advice. First, read, read, read, especially stories in the genre you wish to write. As you read, take note of the techniques that successful writers use to tell their stories, and incorporate them in your own writing.

Next, remember that stories are never about events—they’re about characters who are affected by those events. With this in mind, observe the audience for whom you’re writing and record the things you see and hear and feel.Imagination plays a very small role in my own writing.I draw from my personal experiences and from the experiences of others whom I’ve met. The characters of all genres—whether fantasy or mystery or science fiction or whatever—are essentially beings who inhabit a world that requires building, and what better way to do that than through observation of your ownworld.

Finally, understand that there’s no such thing as writer’s block. Whenever I find myself stuck in a manuscript (and this happens far more often than I care to admit), it’s always because there’s something I don’t fully understand and I need more information to help me work through it. For example, when draftingThe Space Between, I had no idea how to write the scene where Jace finds his older brother lying dead in their family’s garage, having shot himself with their father’s hunting rifle. I couldn’t even begin to imagine how Jace might respond in that situation. (Let’s face it, it’s a horrific moment—his brother’s body lies crumpled on the concrete, brain matter all over the wall behind him.)After agonizing over that scene for days, I did the only thing I could do at that point—Iabandoned it, putting an X on the page and movingon to the next part of the story. But I’m convinced that my writing brain is always looking for solutions and,shortly after that, I had the good fortune to meet a person who was in Manhattan near the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001, when the planes struck the twin towers. The experienceshe shared with me directly informed my writing of Jace’s moment, and my editor later called it one of the strongest scenes in the whole novel. Remember, writers are never blocked—they’re simply lacking the knowledge they need to continue.

EDITOR’S CHOICE

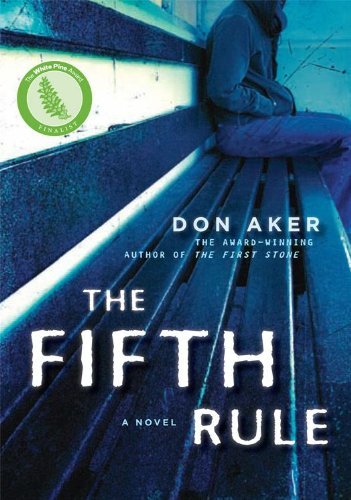

The Fifth Rule is a powerful, emotional story of love, redemption, and resilience with engaging characters and gripping conflicts.

Don Aker’s The Fifth Rule is a compelling tale of redemption and personal growth. With vivid character development and a gripping narrative, the story explores themes of love, forgiveness, and resilience. Reef’s struggles are raw and relatable, while Leeza’s perspective adds depth. The intertwining conflicts create dynamic tension. A heartfelt read for anyone who enjoys emotionally-driven, character-led stories.